A promise of work for a £28 ticket

Angela Cobbinah meets one of the last surviving passengers of the historic voyage of the Empire Windrush in 1948

Friday, 14th October 2022 — By Angela Cobbinah

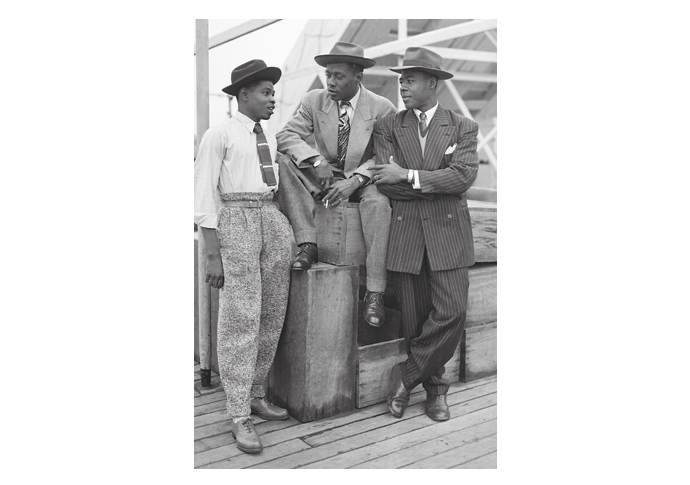

John Richardson, pictured far right, with John Hazel and Harold Wilmot (left) arriving in the UK on the Empire Windrush from Jamaica in 1948. Photo: Douglas Miller/Getty Images, courtesy of Windrush Foundation

STANDING elegantly in his black pin-striped suit and trilby hat, John Richardson looks the very epitome of cool despite having spent a month sailing the 3,000 miles from Jamaica to England on the Empire Windrush in 1948.

The beautifully arranged photograph of him beside fellow passengers John Hazel and Harold Wilmot has become an iconic image, symbolising the spirit of what has become known as the Windrush generation.

“Coming off the boat we all got sharp, everybody dressed up as if we were going to a Christmas party,” recalls John, who had bought his bespoke suit while working as a farm labourer in the US during the war.

“The photographers were all over the place looking for stories and one came up to us asking if we’d like to pose for the camera. The funny thing is, I had never met the other two and I never saw them again.”

Now aged 97, he is one of only two surviving passengers who travelled on the ship and is to be the subject of a documentary by the Windrush Foundation marking the 75th anniversary of its arrival next year.

Sporting a bright blue and white checked shirt and red braces, he remains as stylish and as unruffled as ever. Looking back over the decades, he brushes off the hostility he encountered as a newly arrived migrant with a shrug of the shoulder.

“We thought we were coming to the Mother Country but it didn’t work out that way,” he says, speaking from his home of 60 years in Kensal Rise. “It didn’t bother me. I just wanted to work, have somewhere to live and something to eat. I did all of that and have no regrets.”

When John bought his passage on the Empire Windrush, he had not long been back from his two-year stint in America. Advertised in the Daily Gleaner, the cheapest tickets sold for just over £28, the equivalent of about £1,000 today, holding the promise of work in Britain’s post-war reconstruction.

John Richardson came to the ‘Mother Country’ on the Empire Windrush in 1948. Photo: Angela Cobbinah

“It was a lot of money but I didn’t have any hesitation about going. Jamaica was as poor as it was when I left it and I just need to get out and earn money.”

He hailed from Portland on Jamaica’s north-east coast, the eldest of five children, and his father was a banana farmer who made just enough money to get by. Aged 22, John was listed in the ship’s records as being a carpenter, the trade he learnt on leaving school at the age of 14. On board he felt a sense of adventure, thoroughly enjoying the convivial atmosphere. “I didn’t get bored, it was something new. You meet people, you talk with them, and they tell you some good stories – all lies,” he chuckles.

On a misty summer’s morning just under a month later, the Empire Windrush finally steamed up the Thames to Tilbury. Many of the other passengers were returning to England after a war-time stint in the RAF and already had accommodation lined up. Knowing no one in the UK, John spent his first two weeks at the Clapham South Deep Shelter, a former bomb shelter during Blitz that had been set aside for Windrush arrivals.

One abiding memory he has of it is the deafening noise of the Northern line underground trains passing above them. “Our bunks were only one level below the tracks and we were woken up each morning at five when the service resumed. But you get used to it,” he recalls with his customary nonchalance.

Most people were directed to the labour exchange in Brixton to get a job but John got his by chance after bumping into a friendly Welsh railwayman. Within a few days he was in Orpington in Kent, where he would work maintaining trains for the next seven years.

After living here and there, he finally settled down in Notting Hill, scene of the 1958 race riots. John remembers the tensions. “It was hostile but it was on both sides. It is not a nice thing to say, but the riots made a big difference. They respect us more because they realised we would fight back if they took liberties. Things gradually improved.”

John bought his house, a substantial one at that, for around £3,000, setting up home with his wife Lynn, a fellow Jamaican whom he’d met in London. Steady and hard-working, he transferred jobs to a railway depot in Battersea, where he continued to service trains until his retirement.

For entertainment, the Paramount Dance Hall in Tottenham Court Road became a favourite haunt. He also played cricket for British Railways and local West Indian teams and in 1971 he became a founder member of the Learie Constantine Community Centre in Willesden, named after the famous Trinidadian cricketer.

“We didn’t have anywhere to go – white people didn’t want you at their place,” he explains. “The most place we went to was the Paramount. If we have our own dance police come in and raid us and thief our liquor.”

Currently under reconstruction, the centre is still going strong and John remains an active member.

The years flew by and he forgot all about the Empire Windrush. “As a matter of fact, I only remembered it when I read in the paper that it had burned down and sunk [in the Mediterranean in 1954].”

But in 1988, he was invited to attend a commemoration of its arrival 40 years previously by Sam King, who had sailed on the boat with him and was now the mayor of Southwark. In 1998, John got to meet Prince Charles at St James’ Palace for the 50th anniversary, and in 2018 sat among VIPs at a celebration in Westminster Abbey marking the 70th.

“I’m too old for emotion and I don’t go head over heels about it. But If I am still around I will attend the 75th anniversary next year,” he says before adding with a flourish: “It wasn’t easy when we came up but I made a good choice.

“It was £28 well spent.”