Artists’ muse back in the frame

A new play tells the story of Fanny Eaton, who sat for several leading Pre-Raphaelite artists but died in obscurity, writes Angela Cobbinah

Friday, 14th October 2022 — By Angela Cobbinah

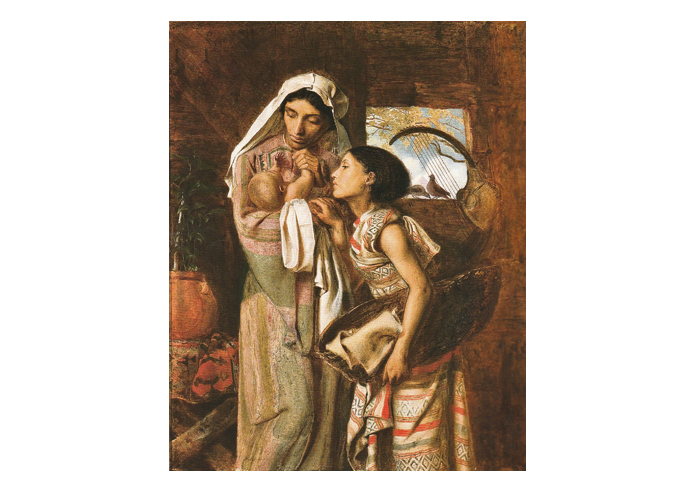

The Mother of Moses by Simeon Solomon. (Courtesy of Deleware Art Museum)

HER image graces some of the most famous paintings of the Victorian age but Fanny Eaton’s contribution to art history has been largely brushed out.

Born in Jamaica and raised in King’s Cross, Eaton sat for the likes of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Simeon Solomon, leading Pre-Raphaelites whose art set out to defy convention in both style and content.

While other models of the day have become historic figures in their own right, Eaton died in obscurity and lay for years in an unmarked grave.

Now a new play opening next week aims to put the record straight, allowing Eaton to tell her own story with the help of some of the masterpieces she appeared in.

Called Out of the Picture, the one-woman show has been written by art historian Angela Bolger, who co-directs with the actress Faith Tingle-Bartoli.

“Other Pre-Raphaelite muses like Lizzie Siddal and Jane Morris have been studied and had books, plays and films about them, but not Fanny,” says Ms Tingle-Bartoli. “Although she inspired many artists with her grace and beauty, her story has never been told.”

Eaton was born in 1835, the daughter of Matilda Foster, a former slave. Her father is thought to have been an English soldier stationed in Jamaica who died shortly after her birth.

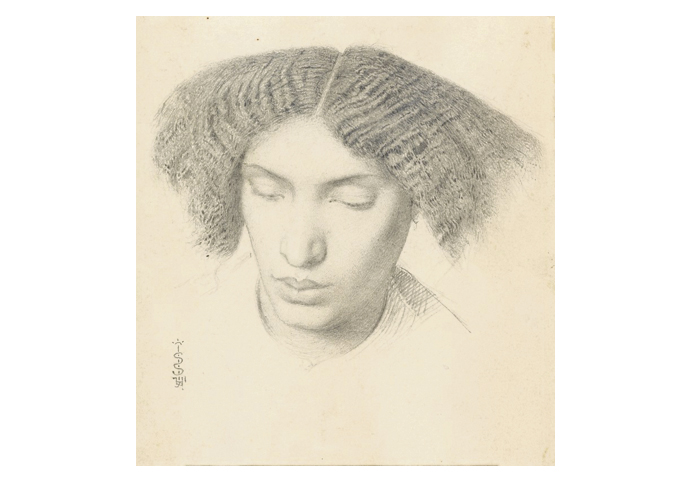

Solomon’s study for The Mother of Moses. (Courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum)

A few years after Emancipation in 1838, the young Fanny accompanied her mother to England and the two settled in St Pancras. Following her marriage to James Eaton, a horse-cab driver, she moved to Tonbridge St, King’s Cross, around the corner from her mother’s in Cromer Street, and made a living as a cleaner. It was the 1850s.

The play speculates that it was her line of work that first brought her into contact with Solomon, a brilliant young artist who lived with his family in John St, Bloomsbury, a 10-minute walk away.

“It may be that Fanny worked for them or in the house of one of their neighbours and was spotted,” says Ms Bolger.

“I don’t think she set herself up to be a model. She was spotted because of the sort of art that was being painted at the time. It was a tumultuous and important period in history and artists wanted to use Fanny in their response to events like the American Civil War and Indian Uprising.”

Solomon made a number of drawings of her that are now held at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

These came to form the basis of Eaton’s debut in a painting, as both the mother and daughter figure in Solomon’s Mother of Moses, which was a direct reference to slavery in the context of the captive Israelites.

The Beloved (The Bride) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Fanny is featured second from right at the rear of the painting. (Courtesy of the Tate Gallery)

Eaton went on to model regularly for art classes at the Royal Academy, where her good looks would have attracted the attention of other well-known artists.

According to RA petty cash receipts for 1860, on one occasion she received 15 shillings for three sittings, about £450 in today’s money. Having already given birth to two of her 10 children, this would have been a welcome addition to the family income.

Painters saw her mix of African and European features as an opportunity to portray any woman they deemed exotic, whatever their origins. “But they always painted her in a very noble and dignified way,” says Ms Bolger, who specialises in the study of artists’ models. Rossetti, who had exalted notions of female beauty, was particularly struck by her, telling Ford Maddox Brown in a letter that Eaton had a “very fine head and figure”.

Rossetti used her in his biblically-inspired 1865 painting, The Beloved, one of the works that Eaton – performed by Samya De Meo – talks about in the course of the 45-minute play.

Other paintings she pauses by include Albert Moore’s haunting The Mother of Sisera, another Old Testament figure; A Young Teacher by Rebecca Solomon, which earlier this year sold at Sotheby’s for £306,000; and the Head of Mrs Eaton by Joanna Mary Wells, in which she appears majestically in her own right.

Actor Samya De Meo in one-woman show Out of the Picture

As she looks back on her life as an artist’s muse, 12 other characters pop up, including Rossetti, her husband and two art critics, all played by De Meo.

Eaton inspired more than a score of artworks but her time as a model was short-lived. After 1867, she more or less disappeared from view, largely, the playwright believes, because artists had moved on to different subjects and styles. But as a result of her modelling work, the family were able to better themselves and move out of King’s Cross to the much more salubrious Pentonville, then Kensington. In 1881, tragedy struck with the death of her husband and Eaton took up work as a seamstress.

Later, as resourceful as ever, she worked as a cook on the Isle of Wight for a wine merchant and his wife. In 1911, Eaton was living in Hammersmith with one of her daughters and her family. She died aged 89 and was recently discovered to be buried in the local Margravine Cemetery. Last month, a memorial on her grave was unveiled by her great-grandchildren.

“Of all the muses I have studied, she is the most interesting character of the lot,” says Ms Bolger. “Although she has been the subject of academic interest in recent years, there isn’t much information about her, other than she appeared in all these pictures. Even her descendants didn’t know the facts of her life. In the play she is stepping out of the picture to talk to us today.”

• Out of the Picture is at the Beethoven Centre, Third Ave, W10 4JL, on October 17 and October 21. 7pm. Free but booking required via elysse@queensparkcommunitycouncil.gov.uk or call 020 8960 5644 Mon-Wed/Fri 10.30-5pm