Boys are bombarded with misogyny – we must act

Headteacher's comment piece as part of our 'Stop The Trolls' special edition

Friday, 7th March 2025 — By Izzy Jones

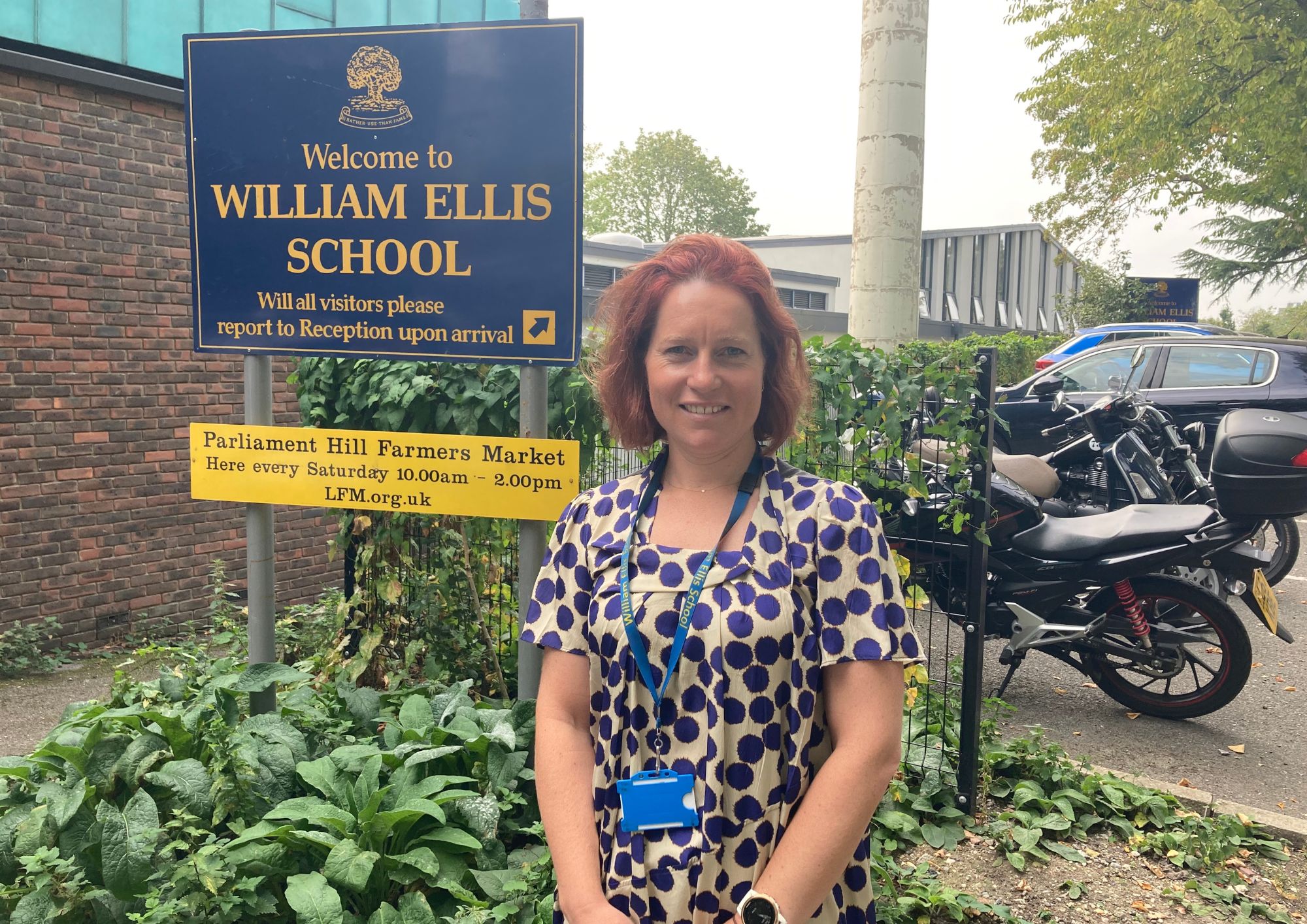

Izzy Jones is the headteacher at William Ellis School

WHAT do I know about the challenges of being a teenage boy?

I’m the first female headteacher of a well-established boys’ school – when boys’ education is an increasingly rare offer, challenged to redefine itself.

I’d experienced secondary school as one of few girls in a boy-dominated classroom, I’d played enough high-level sport to understand what a “laddish” culture felt like, and like most women, faced times when I’d needed to assert myself against casual misogyny.

Those experiences are important, but not the same.

Boys in the 2020s are in a singularly tough place: for their whole lifetimes, girls are likely to have outperformed them at school, and traditionally male, school-leaver job opportunities are diminishing.

Post “MeToo” and #EveryonesInvited, they are aware that certain words and attitudes about women should neither be used nor held.

Yet their social media feeds, whether they seek it out or not, are littered with Andrew Tate and others promoting ideas about women as property, inferior, and objects for male use, justifying control, submission, and violence.

An American president recorded saying how he wanted to handle a woman by what part of her body.

And, though they won’t admit it and we don’t like to ask about it, clickbait soft pornography.

They are children, and this is too much.

Ofsted’s 2021 national report highlighted problems with teenage boys’ treatment of girls – casual misogyny and derogatory language – requiring action from schools.

They told us and other boys’ schools they inspected after this that we needed to do more to address it.

Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation (2024) highlights powerfully the current tendency to under-protect children online.

More powerfully, our boys told us that they wanted it to be addressed. And they set us some real challenges.

They wanted constructive guidance about how to relate to their female peers in a way that was respectful, kind and caring rather than predatory or derogatory – not just being told what not to do.

They wanted us to know that seeing and hearing those attitudes made them feel uncomfortable.

In that situation, what could, and should they do?

They were children, asking us to help them do better and support others the same.

Teaching is such a privilege because teenagers can be such positive, powerful agents for change.

We were all once the young person who wanted to change the world.

What can institutions do?

We can have rules and sanctions, explicit policies and statements against misogynistic, homophobic or other derogatory language and behaviour.

But creating a positive culture requires collaboration – allowing boys to authentically articulate why such attitudes are unacceptable and harmful to them.

We must demonstrate how figures like Tate damage boys’ mental health: not just his views on women, but also health and exercise prohibit any show of physical or emotional weakness, an ask for help, or admission of mistakes.

This undermines our efforts to create happy, healthy successful futures for young men.

We also must accept that social media is an advanced and savvy industry with complex technology and profit motives.

We have partnered with Middlesex University to co-construct an education programme that teaches about algorithms and social media profiling.

This involves co-delivery by older students working with those in younger years.

We need to understand that as teenagers, their biggest influence is each other, not the adults around them.

Facilitating rather than preventing that dialogue is crucial, including opportunities for work with neighbouring schools.

While I’m heartened by the increasing global momentum toward regulating social media and online content for young people, they need to understand how it can manipulate and exploit their weaknesses.

They may be the generation regulating a new online world for the mid-21st century, requiring skills we must provide now.

As individuals and communities, we must maintain open and non-threatening communication with teenage boys.

Their experiences are often more nuanced than a simple choice between good and bad.

Rather than showing anger that causes them to withdraw, encourage them to share what they are seeing online without judgement, and model thoughtful adult social media use – there are now a wealth of resources that can help us to do this.

We must provide and encourage opportunities to build interpersonal relationships, social and emotional skills, away from screens.

Playing outdoors, doing adventurous things, exploring your creative side – these are all such an important part of growing up.

We need to encourage them to say yes to residential trips even if it will be wet, play afternoon basketball even if their legs will feel tired and sweaty, attend drama club even if they will be embarrassed the first time.

These are all visible and real risks to a teenager, and to a parent.

But the risks of disappearing into a private online world from the bedroom are perhaps larger and more sinister.

There is still so much more to do.

But young people, including boys, have so much to offer in this space.

Let’s bring out the best in them, and create a better future together.

. Izzy Jones is the head at William Ellis School