Camden’s very own Queen Vic

In the latest of his series on eminent Victorians in the borough, Neil Titley gets all royal on us

Friday, 18th December 2020 — By Neil Titley

George Hayter’s coronation portrait of Queen Victoria

ALTHOUGH famously in 1835 her uncle King William IV is reputed to have called for refreshment at the eponymous pub in Hampstead High Street, Queen Victoria’s (1819-1901) involvement with Camden taverns is not so well known.

Shortly before her accession to the throne in 1837, Victoria was travelling in a coach at the top of Highgate West Hill when the horses bolted down the 1:5 gradient. The landlord of the Fox under the Hill (later demolished) dashed out and managed to control the maddened animals, thereby saving her life. Sitting in the forecourt of his pub afterwards, the future sovereign asked him what he desired in return. He asked for and received the right to hang the royal coat of arms outside his tavern. However, the landlord was ever afterwards so tortured by the thought of what largesse he might have requested that he fretted himself into an early grave.

Victoria’s success as a monarch stemmed in part from her identification with the burgeoning British middle class. She disliked the aristocracy and had the perception to realise that their power had waned, while to her, the working class were virtually a closed book. Instead she emphasised “family values” and insisted on high standards of sexual morality.

Whether in the case of her subjects this ever rose above vociferous hypocrisy is debatable but on her part it was genuine. Her rigidity was, to some extent, a rebellion against the well-publicised debaucheries of her uncles, led by King George IV.

She was fortunate that in her marriage to Prince Albert in 1840 she found a spouse who was equally appalled at his own upbringing and was happy to join Victoria in her desire for “a strict court and a high attitude”. He came from a family, the German Dukes of Saxe-Coburg Gotha, whose main contribution to society appears to have been syphilis.

For 20 years, the royal pair enjoyed a generally idyllic life, with Albert becoming an important political advisor as well as involving himself in all manner of social improvements – the development of the South Kensington museums known as “Albertopolis” being a lasting monument.

In a local example of his sense of civic duty, when the Roslyn House home for girls orphaned by the Crimean War was moved to Vane House in Rosslyn Hill, Prince Albert personally led the girls to their new residence.

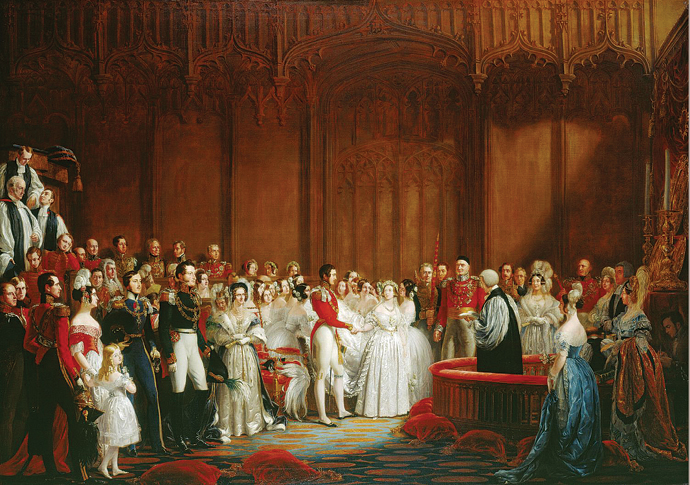

Hayter’s painting of the Queen’s marriage to Albert

Victoria was never fond of Buckingham Palace as it was overrun by rats, and preferred to stay in the Highland castle of Balmoral. After Albert had improved the building by converting it into a sort of German Schloss and papering the walls in tartan, they settled into a lifestyle that became known as “Balmorality”. The courtiers were ordered to wear kilts, Victoria learned Highland dancing, and Albert laboriously studied Gaelic.

One of Victoria’s main principles was a strong belief in frugality. (She saved a fortune out of her £400,000 a year Civil List pension by banking it almost untouched – this money provides the basis for the wealth of the current Royal Family.) But to avoid unnecessary expenditure, Victoria rationed the fires. As a result, Balmoral proved to be so cold that Albert, who was prematurely bald, was forced to wear a wig.

While performing her round of civic duties Victoria visited Cambridge. Until the 1890s, when the city sanitation was modernised, all sewage went directly into the River Cam. The official tour, led by the Master of Trinity, happened to cross over a bridge. Victoria, looking down at the water, noticed some pieces of paper floating downstream and asked what they were. The Master, thinking quickly, replied:“Those, ma’am, are notices that bathing is forbidden.”

Although comic at the time, this negligence over Cambridge sanitation was to have tragic consequences.

In 1861, Prince Albert appalled by gossip that his son the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) had slept with an actress, travelled to the university to confront him. During the visit, Albert caught typhoid fever and died.

Victoria was devastated. Entered a state of mourning that effectively lasted the rest of her life, she avoided public appearances. This seclusion earned her the nickname “the Widow of Windsor”.

Victoria’s reign lasted 63 years and she was acknowledged as an intelligent and – eventually – a beloved monarch. She had been fortunate in her mentors, who as well as Prince Albert included two very sympathetic prime ministers (Lord Melbourne and Benjamin Disraeli), and two highly unlikely characters who proved to be her mainstay.

The Highlander John Brown held an extraordinary position in Victoria’s household – partly servant, possibly lover, and definitely drinking companion, (whisky was their preference). After his death she relied heavily on a Muslim Indian called Abdul Karim, or “the Munshi” who taught her Urdu. Victoria dismissed criticism of her choice of companion as racial prejudice.

However, even later in Victoria’s life, when she returned to some measure of public visibility, the Queen was still in thrall to Albert’s memory. Disraeli, on his deathbed, famously declined a visit from his sovereign: “No, it is better not,” he said. “She will only ask me to take a message to Albert.”

• Adapted from Neil Titley’s book The Oscar Wilde World of Gossip. For details go to www.wildetheatre.co.uk