Canal knowledge: an adventure through the waterways of Venice

Conrad Landin finds AJ Martin’s latest novel his most mature to date

Thursday, 23rd January 2025 — By Conrad Landin

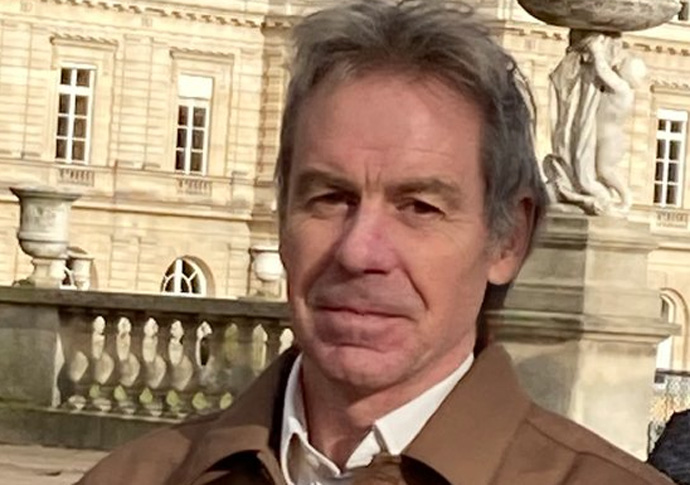

Andrew Martin, author of The Night in Venice

“OF all the cities of the world,” wrote Henry James, Venice “is the easiest to visit without going there”. Yet the alien, performative, and dream-like qualities of this city – an historic republic in its own right – also make it the easiest to be absent within while in residence.

For Monica, the 14-year-old orphan protagonist of The Night in Venice, the city is more still a gateway to a reckoning: with her past and future, and with her uneasy relationships with truth and morality.

She arrives in the city in 1911, in the care of her governess Rose Driscoll – always simply “Driscoll” and “providing living proof that excitement was not guaranteed to occur”.

The morning after her first night’s stay, Monica awakes to the recollection of defenestrating Driscoll into the canal below. Fearful of discovering whether this is dream or reality, she flees their palazzo.

And expecting imminent arrest, she has a day of both deep reflection and wild acting out ahead.

What follows is a picaresque adventure not only through the waterways and piazzas of Venice, but through the streets and squares of north London too. Monica, after all, has descended from her parents’ luxurious pile in Hampstead to a dank flat in Holloway Road – via the bohemian Pond Square townhouse of her uncle Leo, since killed by a tram.

Martin treats us to a dazzling psycho-geography of Camden and Islington, from Rosslyn Hill to Upper Street. There is a fine inventory of the Edwardian shops of Holloway Road, but better still are the accounts of AJ Martin’s own neighbourhood of Highgate, with its “stink pipe” a hub of activity for miscreant schoolboys.

Martin’s 1911 is refreshingly modern. Monica and her acquaintances may not have smartphones or vapes, but they navigate the same worries and obstacles as any contemporary teenager, and interact in the timeless teenage fashion that renders everything both inconsequential and life-defining.

As the somewhat plainer Andrew Martin, the author has been responsible for the Jim Stringer railway detective series and scattered stand-alone novels. His accomplished non-fiction titles, meanwhile, draw nostalgically upon bygone guidebooks while exhibiting a masterful ability of observation.

Both these qualities are on display in The Night in Venice, with Hare and Baddeley’s stuffy but exuberant Venice the primer of choice. And they help Martin deliver that rare thing: a good grown-up book about children.

For while the teenage Monica is wiser than her years, she is also younger than them – something recognised not only by the adults around her but by herself too.

Some of her violent outbursts offer just deserts for her victims, others less so. She is often dislikable – her snobbery is off the scale, for one – but remains sympathetic throughout.

The Stringer novels show that Martin has a Simenonian gift for atmosphere, but his character-building has often been weaker. The Night in Venice is a more mature novel which shows a superior gift for character-building – with Monica, Driscoll and even quite marginal figures rendered as complicated beings, each attribute underscored with very human flaws.

On Monica’s eventual return to London, a truce with Driscoll turns out not to be – with consequences perhaps as severe as those she feared unnecessarily in Venice. By then our trust in the truthfulness of her narrative has disintegrated – but not before we have established the depths that can be plunged when in despair and self-absorption. Martin resists the temptation of cathartic resolution – and his book is all the better for it.

• The Night in Venice. By AJ Martin. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £22