He wasn’t the very model…

In the latest in his series on eminent Camden Victorians, Neil Titley turns his attention to WS Gilbert

Thursday, 28th January 2021 — By Neil Titley

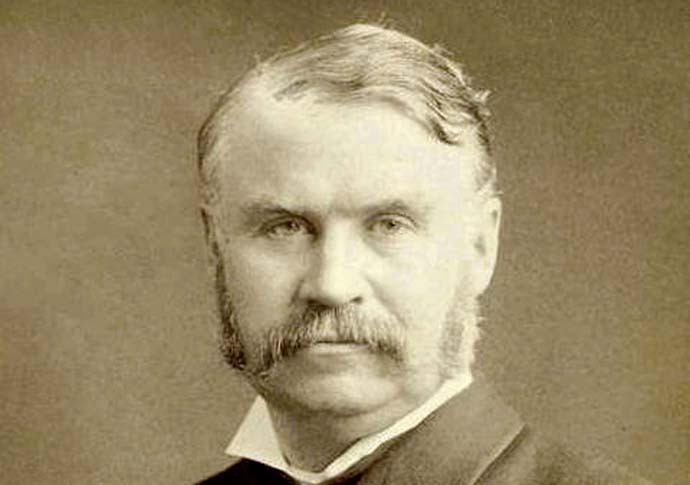

WS Gilbert in 1878

WHEN the fountain in South End Green was first unveiled in 1880, the Victorian musical comedy star George Grossmith (a near neighbour in Maitland Park Road) was among the spectators. After acknowledging the respects of the crowd, he dashed off to the West End for his evening performance as Major-General Stanley in the new smash-hit The Pirates of Penzance by Gilbert and Sullivan.

Sir William Schwenk Gilbert (1836-1911) was a dominant figure in the Victorian theatre. Together with his partner the composer Sir Arthur Sullivan, he created an unforgettable series of comic operas and formed the greatest English popular music collaboration until (arguably) the arrival of Lennon and McCartney.

Gilbert had started his career as a junior barrister but failed dismally. After one particularly inept defence that had earned his client an 18-month sentence with hard labour, the client removed her shoe in the courtroom and hurled it at his head. After four years at the bar, Gilbert had averaged five clients a year and had totalled £75 in fees.

Gilbert’s real talent lay in his mastery of language. Although his plays and poems achieved some recognition, success in this field came slowly. Then in 1875, on the suggestion of the promoter Richard D’Oyly Carte, Gilbert joined forces with Sullivan to produce Trial by Jury, the first of a long series of hits. Gilbert’s task was to provide the libretto as he had no ear for music. He said that he only knew two tunes – one was God Save the Queen and the other one wasn’t.

Their work became so popular that it was pirated ruthlessly by American producers. When D’Oyly Carte lost a copyright action in the US courts trying to defend HMS Pinafore, the judge stated that “no Englishman possesses any rights which a true-born American is bound to respect”. An American impresario suggested instead that Gilbert could write an American version of Pinafore. Gilbert, still fuming over the court case, responded by fitting a new lyric to his song. It originally read:

“Though he himself has said it – And it’s greatly to his credit – That he is an Eng-lish-man…” etc.

The new version read: “Though he himself has said it – Tis not much to his credit – That he is A-mer-i-can” etc.

The idea was dropped.

WS Gilbert, the Ironmaster at the Savoy

Although they were an ideal match in some ways, Gilbert’s political satire often irritated those in the circles of privilege at a time when Sullivan was eager to socialise with them. The result was that while Sullivan was knighted in 1884, it was another 24 years before Gilbert was similarly honoured.

By 1890, boredom with work they both considered beneath them, combined with quarrels over finances, broke the alliance and their friendship ended acrimoniously. During a later revival, they emerged from different sides of the stage to bow to the applause but did not speak to each other, left the theatre separately, and never met again.

Free at last to complete a work of serious grand opera, Arthur Sullivan composed Ivanhoe in 1891. This proved to be a failure, Bernard Shaw describing it as “music in petticoats from the first bar to the last”.

Their business manager D’Oyly Carte (like Grossmith, a Camden habitué – being raised in Dartmouth Park and writing the operetta Happy Hampstead) used the profits from The Mikado to build the epitome of luxury hotels – the Savoy. He ensured its success by hiring the world famous César Ritz as manager and the culinary legend Escoffier as chef (although later Carte sacked both of them for committing large-scale fraud).

Beneath his hearty Tory squire persona, Gilbert was an anarchist with a schoolboy zest for sadistic ridicule. Never an easy-tempered man, no profession roused his ire more than the press.

One day a reporter arrived at his home and asked Gilbert’s butler if he could have an interview. In a voice that resounded through the house, Gilbert thundered: “Tell the bastard to go to hell!!” The butler returned to the front door and announced: “Mr Gilbert is extremely sorry but he wished me to state that extreme pressure of work precludes him from the pleasure of seeing you this morning.”

Despite a happy marriage to Kitty Gilbert, his lack of gallantry toward women was notorious. When a lady of advancing years told him that she “couldn’t remember the Crimean War”, Gilbert’s reply was: “Don’t you? I’m sure you could if you tried”.

A girl in his opera company complained that a man had made advances to her, putting his arm around her waist and calling her “a pretty little thing”. Gilbert consoled her with: “Never mind, he couldn’t have meant it”.

After his retirement, he felt unleashed from a lifetime of writing works that appealed to middle-brow taste. This new freedom found expression in dozens of unprintably filthy limericks and a pornographic play in typescript that delighted his fellow West End clubmen.

In 1911, after diving into a lake at his Harrow home to rescue a girl in difficulties, Gilbert suffered a heart attack and himself drowned. The girl survived.

- Adapted from Neil Titley’s book The Oscar Wilde World of Gossip. For details go to www.wildetheatre.co.uk