How Asquith railed against racism in bid to clinch Euston job

Railwayman who fought for role made employment history

Friday, 3rd October 2025 — By Dan Carrier

Asquith Xavier at work in Euston Station

IT was the spring of 1966 when British railwayman Asquith Xavier saw the advert for a job at Euston station.

The father-of-seven was a passenger guard at Marylebone and earning £12 a week. The new position offered £50 a week and so he put in his application, sat back and waited for a letter telling him when he could go for an interview.

What happened next cast a light on the daily racism workers faced – and how the rail unions came to terms with systematic bigotry among their workforce and evolved into powerful advocates for change.

Mr Xavier was originally from Dominica and had moved to London for work in 1958. He lived in Ledbury Road, Paddington, and won a position as a guard on the short train runs from Marylebone out to the home counties. British Rail paid bonuses to guards on longer routes for the extra miles travelled, so Mr Xavier applied to transfer over to Euston where a guard’s salary was significantly higher.

He was not the only guard who saw the job advertised and fancied a change. His line manager Tony Donaghey, who was Irish, also applied for the role. Tony was offered a position, while Asquith was not.

What followed would help change unions’ approach to workplace racism, and help bring in the 1968 Race Relations Act, to cover occupational discrimination.

Mr Xavier was sent a letter from the National Union of Railwaymen Staff Committee which said union members at Euston were not “prepared to accept the transfer of coloured staff”.

It emerged that a network of shop stewards were running a closed shop and instigating a racist hiring policy.

Mr Xavier was attacked personally, receiving an unsigned letter that told him: “When we have finished with you at Euston, we’ll send you back to the jungle.”

Outraged by the decision, Mr Xavier rallied colleagues for support. Mr Donaghey had faced discrimination because of his Irish heritage – he had been turned down for rail jobs before due to this – and when he was told that Mr Xavier had been refused the job because of racism, he declined to take up the role he was offered in solidarity.

The issue came a year after the first Race Relations Act had put in place measures to combat discrimination in public places but not in work places.

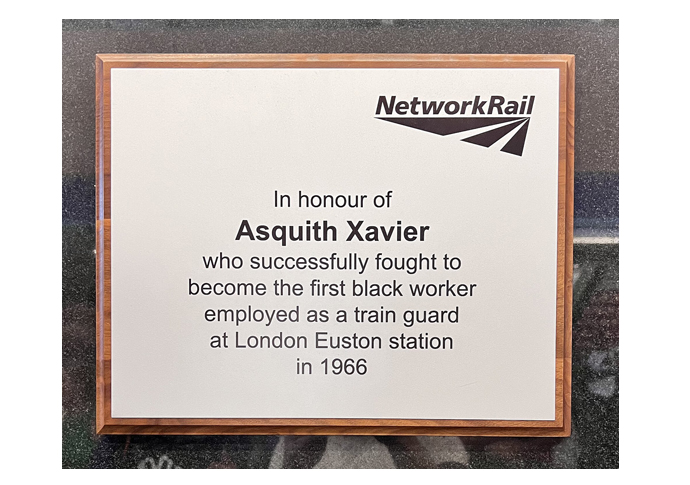

A plaque dedicated to Mr Xavier

The NUR at Marylebone took up Mr Xavier’s case and were joined by other human rights and anti-racist groups.

After publicising the issues and holding the railway unions to account, British Rail were forced to act: it would result in July, 1966 with the railway body making sure there were no colour bars at any of their stations – and in August that year Asquith Xavier began work at Euston.

On Tuesday August 16 1966, The Daily Express covered Mr Xavier’s first day at work in his new role. They described how fellow workers “rolled out the red carpet”, adding: “Management and men competed in their efforts to make him feel at home. Mr Xavier, 45-year-old Notting Hill man with seven children, smiled and said ‘Thank you’.”

On the day Mr Asquith began work he was met by Alfred Duffield, the chair of a union committee that had originally said they would not work alongside black employees.

Meeting Mr Xavier on platform 14, Mr Duffield told gathered reporters: “Did you see any trouble this morning? Not a sign. And that’s how it will be.”