How building campaigner Vic played a key role in making sites safer places

In appreciation, friendship and respect for Vic Heath: a Camden hero

Wednesday, 28th May 2025 — By Linda Clarke

Victor Heath: September 3 1932-April 26 2025

ON April 26 Vic Heath, born in Arlington Road, Camden Town, on September 3 1932, died. He was a long-standing friend and comrade to me and many others, one who fought relentlessly to improve conditions in the building industry, in Camden, and in society.

Fortunately, it is not necessary to rely just on my words to give a flavour of just what an important contribution he made, his warmth, humour, solidarity for others, and many activities to fight injustices.

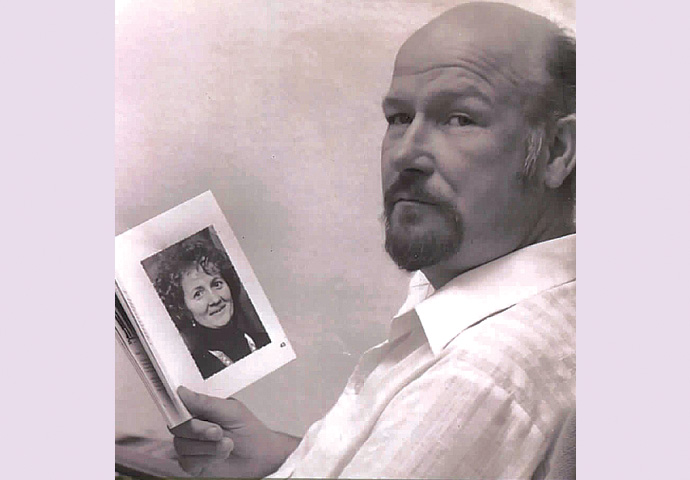

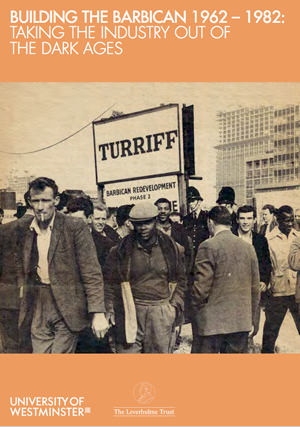

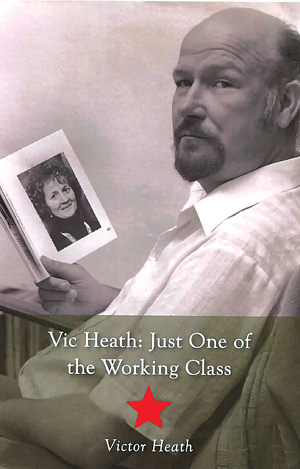

Vic himself wrote a book, Vic Heath: Just One of the Working Class, an as-yet unpublished sequel to this, and a small book of poetry published in 1974, as well as giving interviews, including for research I have been involved in on the building industry; he featured heavily too in a pamphlet Building the Barbican 1962-1982: Taking the Industry out of the Dark Ages (https://files.libcom.org/files/Barbican-pamphlet.pdf).

Born before the war in the heart of Camden Town and growing up during the war Vic describes in the pamphlet how:

“There were loads of buildings still knocked down, bombed, and we used to play on the bombsites, the Black Cat, on the corner of Morning Crescent, which was the place they used to make the old Black Cat cigarettes, and they dropped loads and loads of fire bombs there.”

Vic featured in the Building the Barbican pamphlet

His father was a postman, and his mother worked a small munitions factory during the war, and later as a cleaner. Leaving school before he was 14, Vic then “went and got a job. I worked with my brother, who was a carpenter, I gave it up … I didn’t become an apprentice.”

Instead, during the 1950s, he worked on various building sites as a scaffolder around Camden, joining first the Transport and General Workers Union and then the AUBTW (Amalgamated Union of Building Trade Workers), and becoming a scaffolders’ shop steward on most sites he worked on, “almost as soon as I walked on the job”.

In 1954 Viv met and married Vera, who survives him, and their son Gary was born in 1959, but sadly he died of cancer in 2006, aged only 47.

In 1965 he was employed on the Barbican’s Turriff site, and was there for three and a half years, as it grew from employing about 150 up to 500 workers. Vic, who was a scaffolder steward and chairman of the works committee, would recount the appalling working conditions they were confronted with to begin with, including the lack of proper toilets or any washing facilities:

“We had a mass meeting, and we took the decision that we needed proper flush toilets, and the management said they weren’t prepared to construct flush toilets.

“So we said, what we’ll do is use the toilets at St Paul’s Cathedral – a fair little walk up the road, they had public toilets there. One lad would go off up the road towards St Paul’s, and then one, after a short interval, would go behind him and so on, and within half an hour, near enough half of the men on the site were walking up towards St Paul’s, and, as they finished in the toilet and walked back down again, there was somebody to take their place – we did that for three or four days…

“The management couldn’t do anything about it because, within the rules, it said we were entitled to proper toilets, they conceded, once again, and constructed, about six flush toilets and six urinals, and then there was a trough in the middle with taps, so you could all wash your hands.”

The next battle was to build “a proper canteen, with a kitchen, where you’d get a breakfast”. Again, this was a success and “in the end, they built a proper canteen, 50 feet long by 40, with a proper kitchen, with young women working in the kitchen cooking us breakfasts”.

Vic found the main problems on sites were down to bad management: “They had this civil engineering idea in their head, and they thought they could just ride roughshod over blokes on the site.”

As well as fighting to improve conditions, the Turriff workers also supported the dispute on the adjoining Myton’s Barbican site when they needed help:

“We’d stop work and go over the road and back them up … There was a lot of solidarity with building trade workers in London at that time, up and down the country … The camaraderie that you got on those sites, working with so many men, you never forget that tremendous solidarity between ordinary working blokes, every day of your life, and it just sticks with you.”

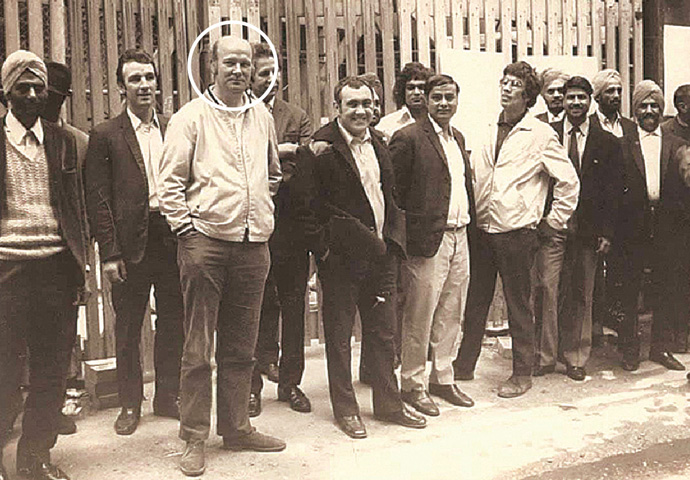

Building workers with Vic Heath (circled) on strike in Leadenhall Street in 1973

Scaffolding was extremely dangerous work, and Vic was clearly a highly skilled scaffolder, though the occupation was not recognised as a skilled one until the early 1970s: “I’d always prided myself in doing a job properly, and everybody appreciated.”

On the Barbican Turriff site, the scaffolders worked up to about 26 floors, but, as Vic explains:

“Because of the weight of the scaffolding, we’d put cantilever scaffolds out, and that was a bit hairy, you’ve got nothing under. You build the scaffold yourself, and you have to rely on your mate you’re working with, and you put a couple of scaffold boards on the tubes that you’d got out and then you’d lie on that and put your ledger underneath and hang it underneath, leaning over the top and looking down 20 floors … the first time I’d ever done hanging scaffolding.”

He argued that a labourer was just as skilled as a carpenter in his particular field, and “without the labourer, the carpenter couldn’t go to work … all the different trades were reliant on the other trades”.

As a strong trade unionist, first with AUBTW and later with UCATT (Union of Construction Allied Trades and Technicians), Vic was very principled, for instance: “I think I only worked overtime, in the whole of my lifetime about once or twice. I always said that we fought for a 40-hour week and that’s what I’m going to work.”

In negotiations on site he would argue for a collective rather than an individual bonus, which was seen as “unfair, because some blokes are getting the good jobs”, so everybody in the scaffolders’ gang got the same bonus. As he explains:

“Well, the general sort of thing was to try and ensure that the lads were working in safe surroundings, and it was very difficult in those days because there was no real serious Health & Safety at Work Act. You’d represent the lads if they didn’t get their bonus right, any sort of problems they had with management, virtually anything – protective clothing, canteen facilities.”

Vic was a Communist, joining the Communist Party when he worked on a Wates’ site in Edgware Road, and only leaving when the party split up. He was also a founding member of the Joint Sites Committee, a solidarity organisation set up in the 1960s with other politically-minded building workers:

“Wherever there was industrial action on any of the sites in the London region, we’d offer our assistance, in most cases, if they needed help, raising money for strikes.”

The committee played an important role in organising flying pickets to stop building sites from working during the 1972 UCATT strike for better pay and conditions.

For all his efforts, Vic was blacklisted, so could not get a job on sites, “the Labour Exchange sent me to all kinds of jobs that I was not suitable for”, and ended up working for London Underground at Acton Works and later Golders Green, with the help of Don Cook, one of the leaders of the 1960 St Pancras rent strike.

Vic Heath: Just One of the Working Class

Finally, in the early, 1970s, while living in Athlone Street near the Holmes Road depot, he succeeded in obtaining a job with Camden Building Department, or Direct Labour Organisation (DLO), first as a labourer and then “made up to a scaffolder” and elected scaffolders’ steward.

With the other stewards he proceeded to organise the DLO: “Half the men working there did not belong to a trade union, so we had a big job on our hands. But over the next few weeks we got everyone in the right trade union for them.” They obtained agreement from the Building Works Committee of Camden Council, chaired at the time by Ken Livingstone, to hold mass meetings:

“They had never had a mass meeting before in the Building Department. We also decided all stewards must come up for re-election once a year, including me. I was elected on the UCATT Regional Council and Committee. I was also elected as the local authority chairman of all trade unions London-based and I became a full-time convenor on Camden. I was also asked to attend the Building Works and Services Committee at Camden Town Hall, I was told that I could claim expenses from the Council, but I never did …We were the only local authority to ever get a 35 hour week.”

As described by Peter Farrell, the painters’ steward:

“We had quite a large shop stewards committee, with many different ideas. Vic was very good at stating laws and agreements. We had many successful struggles particularly equal rights. Vic showed me the article on waterbased paints and supported our struggles over dangerous chemicals. We collected for the miners’ struggle each week. We also supported the Grunswick women sending delegates to support their fight. Vic was a supporter of the Construction Safety Campaign.”

After 20 years with the DLO, when it was reduced from a workforce of 1,300 to just 40, Vic accepted early retirement and then did “things that I’d always wanted to do and never got around to doing. I went to every museum in London, all the museums and art galleries … I spent a year just travelling all round London, after which ‘I got a job with the employment tribunals, and I worked there till I was 70.”

He and Vera later moved out of Camden to Leagrave, near Luton.

What better way to conclude this glimpse at Vic’s life, than an extract from one of his poems:

Building workers went on their first national strike in 1972

For thirteen weeks they stayed out and that’s true

Beating the employers at an age old game

And the workers won a just an right claim

190 building workers were killed in 1972

And these men were workers like me and you

No employer was charged with manslaughter, and why not?

Because the law workers in favour of the employers and their lot.

• Linda Clarke is emeritus professor at Westminster University