‘I spent four years in prison waiting on death row, it makes you reflective'

Andy Tsege has written a memoir of his time being held as a political prisoner in Ethiopia – and tells Daisy Clague of the campaign that won his freedom

Friday, 24th January 2025 — By Daisy Clague

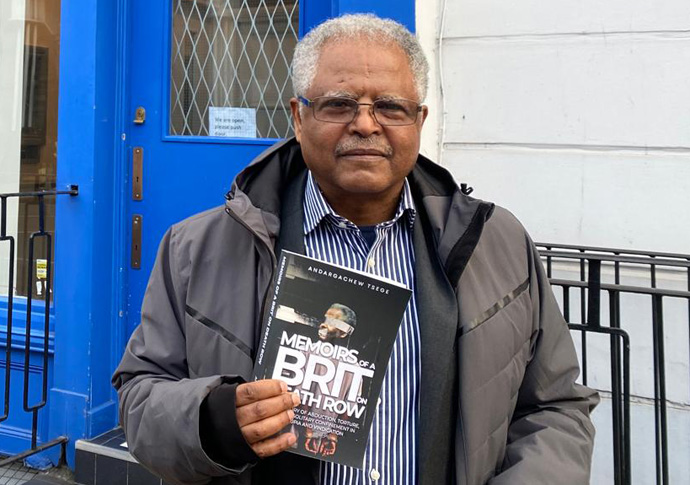

Andargachew Tsege, now 70, with his new book

WATCH OUR HISTORY CHANNEL, UNTOLD LONDON, ON YOUTUBE

WAITING for a connecting flight at Sanaa International Airport in Yemen, Andargachew “Andy” Tsege was approached by a stranger in a blue suit who pulled him in for a hug and kissed him on the cheek.

Mr Tsege was already uneasy about transferring through Yemen, and this was a bad sign.

The stranger was identifying him to someone else.

As a young activist in 1970s Ethiopia, Mr Tsege claimed political asylum in the UK and later became a British citizen.

He continued to criticise Ethiopia’s totalitarian governments and was sentenced to death in absentia in 2009.

Yemen’s close ties to Ethiopia meant Mr Tsege would not usually have flown through Sanaa, but, en route to a meeting of opposition politicians in 2014, he was pressed for time and decided to take the risk.

Shortly after his encounter with the man in the blue suit he was kidnapped and illegally transported to Ethiopia, where he spent four years in prison.

In his book Memoirs of a Brit on Death Row, Mr Tsege details more than a year in solitary confinement and then three years in prison in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, where he shared a cell with two convicted murderers.

“They had no remorse,” Mr Tsege, now 70, recalled.

“They were proud of what they had done. [The authorities] brought them there to make my life hell.

“I had to fight for my life with one of them until the guards came jumping over the wall and separated us.”

Other than weekly visits from his elderly father and, occasionally, British government representatives, Mr Tsege was kept apart from everyone but his cellmates.

Back home in Clerkenwell his then partner, Yemi Hailemariam, and three children were campaigning for his release, together with MP Jeremy Corbyn and Hugh Myddelton Primary School, where two of his children were pupils.

Ms Hailemariam even ran as an independent candidate in Theresa May’s constituency in the 2017 general election to draw attention to her partner’s illegal imprisonment.

Mr Tsege had little knowledge of their efforts, other than a passing comment from one guard – “it’s a bit like ‘free Mandela’ out there” – and a photo, given to him by the British ambassador, of his family standing with a young man on the pitch at the Arsenal football stadium.

Without his glasses on, Mr Tsege thought at first that the young man might be his elder daughter’s boyfriend.

It was only when he got back to his cell that he recognised Arsenal’s then striker Theo Walcott, and realised the British government were not the only ones campaigning for his freedom.

In April 2018, a new prime minister was elected in Ethiopia and Mr Tsege was released with hundreds of other political prisoners on May 28.

Mr Tsege’s family campaigning for his release during their attempts to bring him home to Islington

He returned home to London the following day, met by crowds of supporters, press and his family at the airport.

“I don’t feel that I’m traumatised by this experience because there are a lot of tragic stories in my personal and family history because of political activities,” he told the Tribune.

“This suffering has made me very reflective. Once you look into yourself and laugh at your own weaknesses and vanities, I think nothing bothers you.”

The lack of introspection among Ethiopian politicians is, Mr Tsege added, one of the reasons that each generation seems destined to repeat the mistakes of their predecessors.

“When I get involved in politics, it is because my personal freedom is at stake. It is not really a charity basis – it’s not for others.

“Claiming to be a liberator is very dangerous because you deny the fact that there is something that needs to be liberated within you.

“That’s the problem with Ethiopian revolution. Every time change comes, the change becomes worse than in the past, because nobody would look into their own shortcomings.”

Mr Tsege’s criticism extends to Ethiopia’s current leader, prime minister Abiy Ahmed, the man who pardoned him in 2018.

Once hailed by western powers as a peace-maker, an ethnic civil war broke out under Mr Ahmed’s premiership in 2020, between government forces and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a paramilitary group that had previously held power.

Human rights groups documented crimes against humanity on both sides.

Mr Tsege was still a supporter of Mr Ahmed’s government in 2021, when a Telegraph article alleged that he had made a speech urging government-allied soldiers to kill Tigrayan civilians – something Mr Tsege strongly denies.

He told the Tribune that he was instead calling on soldiers to defend the democratically-elected government at all costs as the TPLF army closed in on Addis Ababa.

Since then, his criticisms of Mr Ahmed’s government have again led Mr Tsege to flee Ethiopia for fear of being imprisoned.

Thinking back to his years on death row, does Mr Tsege feel the British government did enough to bring him home?

“The foreign policy of western governments has never been based on principle,” he said.

“They give lip-service to human rights and democracy and freedom, but if the government that is in power is serving their interest, they would deal with any despot. That’s the track record they have. So when the British government didn’t put much pressure on the Ethiopian government – you know, I’m not surprised. It should not be, but this is the way it is.

“There is an in-built racism within the system, no question about it. But even if a person [imprisoned abroad] is white, if helping him undermines [Britain’s] policy towards that government, they would not do it.”

He added: “They will let an illegally abducted white British person rot in jail if the country that abducted them has very close ties with Britain. They will use this gentle pressure, but no more than that.”

Mr Tsege, who now lives in Richmond, thanked everyone who supported him and his family during their “darkest years”.

He said: “For most newspapers, it’s the big shots that matter – government officials, celebrities. When something happens to ordinary people like me, nobody would know if it was not for local journalism.”

A Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office spokesperson said: “We supported Mr Tsege in Ethiopia and raised his case at the highest level with the Ethiopian authorities at the time.”