Ketamine – but it’s not what you think…

Psychotherapy clinic begins using medicinal version of rave drug to treat depression and addiction

Friday, 23rd January — By Isabel Loubser

Lucy da Silva

KETAMINE could be widely available on the NHS in the next three years, a psychedelic entrepreneur has claimed, as she is recognised as one of the UK’s 100 most inspiring businesswomen.

Lucy da Silva has been running her psychotherapy clinic in Farringdon for 12 months, and has now treated 10 patients.

The centre is one of only a handful where patients can have the ketamine-assisted therapy, which has been privately available in the UK for more than a decade.

The controversial treatment has been used to treat depression, anxiety, PTSD, and addiction issues where traditional therapies have failed.

According to Ms da Silva, of the more than 50 patients she has helped, most have had positive results.

“What I have seen is that 80 to 90 per cent of people go off to live different lives,” she told the Tribune. “It’s quite phenomenal. I can confidently say that most people don’t come back. We don’t want people to come back, we don’t want returning customers whereas a lot of clinics don’t set up that model because they want to keep making money. I want people go off and live a beautiful life.”

Ketamine, which is best known as a popular party drug used for its trance-like qualities, makes the brain more malleable when used as a medicine, Ms da Silva explained.

“Traditionally it’s an anaesthetic. It doles down the fight or flight.”

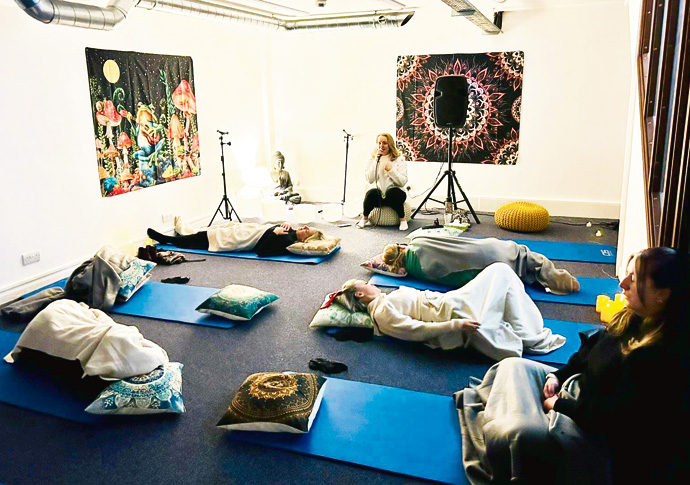

A treatment room

Some experts believe that by rewiring the brain it essentially makes those who have suffered severe PTSD or other mental health issues, more receptive to therapy.

The current cost of the treatment, however, can be too expensive for the majority. Participating in the group programme costs almost £1,000 at the Silva Wellness clinic, which is why Ms da Silva is now working on a new project that will assess how feasible it is to roll it out on the NHS.

“If it’s done in groups, the opportunity to scale is much more than one-to-one. We’re looking at who would need to be involved and the outcome we want is to see that this treatment is something we can scale,” she said. “The next stage is to roll it out and pilot it at some sites in the UK, hopefully towards the summer or the end of the year.”

The therapist added that it was the job of people like her to myth-bust preconceptions about the use of the treatment, specifically any notion that street ketamine and medical ketamine are “the same beast”.

“It is controversial. Because it is new, our job is to educate people so that people who are thinking that we can say ‘look at this, learn about what it does, this is how to make it safe for people’,” Ms da Silva said.

She added: “In the next three to five years we are going to see psychedelic therapy in the UK.

“It will have a massive impact on how we treat addiction.”

AD: YOU CAN GET FREE ACCESS TO AUDIOBOOKS WITH A SIMPLE-TO CANCEL 30-DAY TRIAL OF AUDIBLE

Ms da Silva first became interested in psychedelic therapy when she was searching for treatment for her own complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD).

“In my own personal recovery, after five or six years, I felt like I’d done a lot of work on myself, but I just felt like I wasn’t going further and I needed more,” she said. “I stumbled across psychedelic-assisted therapy in a philosophical way in a medicine community.

“I was fascinated to hear about all these trials with psilocybin and LSD. I had my first experience with psychedelics in a safe therapeutic container and it blew my world apart.

“It showed me that this is healing on another level.”

Warning over Special K street drug

ALERTS have been issued about the dangers of the party drug ketamine – sometimes referred to as Special K, Kit Kat or K – as young party-goers are becoming more and more addicted to it.

A government campaign launched in October last year warned that ketamine use and drug poisonings were the highest on record, with eight times more people seeking treatment since 2015.

The street drug can cause irreparable bladder damage and, in rare circumstances, death.

Friends actor Matthew Perry was among those whose death has been linked to the drug, after it was revealed that his team of medics injected him with ketamine 21 times in the week before he died.

One doctor selling the ketamine as a “medicine” to Mr Perry reportedly texted another, saying: “I wonder how much this moron will pay?”

Some experts have warned that, even in a medical environment, the drug can be addictive, or even dangerous.