Labour pains

Maggie Gruner talks to author Marianne Levy about the cost – physical, mental and financial – of motherhood

Friday, 9th September 2022 — By Maggie Gruner

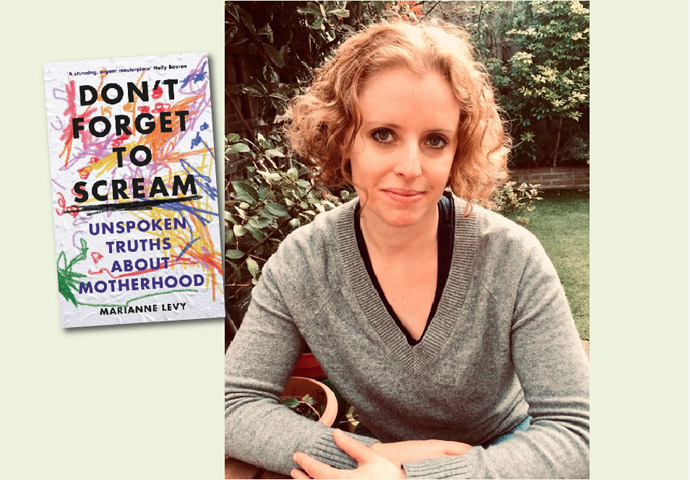

Marianne Levy, author of Don’t Forget to Scream

Marianne Levy was talking about the terror and pain of giving birth to her daughter when a friend raised a hand to stop her, declaring that Marianne’s newborn was “worth it”.

Islington author Marianne was silenced by that phrase, which she heard many times, and she stayed quiet. But no more, as her new book Don’t Forget to Scream, about her experience of childbirth and early years parenting, testifies.

Marianne’s memoir, sometimes poignant, sometimes funny, unflinchingly frank, gives voice to the maelstrom of fear, rage, love and joy, the loss of identity and independence, and the pain that motherhood entails.

She speaks for many. The book grew from essays about motherhood she wrote after having her second child and posted online. The response astonished her.

She told Review: “People were getting in touch to say they had been whisked back to their own early motherhood experiences 10, 20 or even 40 years ago.”

Her daughter was born in 2014 after an agonising 56-hour labour and in 2018 she had her son by caesarean. Afterwards he spent time in neonatal intensive care and Marianne suffered post-operative infections.

Women’s pain is the “ultimate unmentionable”, she writes. And she told Review she thinks this silence, and the attitude that female pain is just natural, or discomfort, has contributed to the inadequacy of maternity services and delay in diagnosing, for example, the painful, debilitating condition endometriosis.

Marianne contends that people don’t want to hear about a bad experience of birth; labour pain is judged “good” and “healthy”; pain from gynaecological procedures is “repacked as discomfort”. When it comes to bleeding and cramping “no one ever wants to know”. Hardly surprising, she asserts, that in the UK the average endometriosis diagnosis takes seven and a half years.

While she was writing, 41 per cent of NHS maternity trusts were deemed “inadequate” or “requires improvement” by the Care Quality Commission.

Referring to the refrain that, however traumatic, labour is “worth it,” she asks: “At what point… would the experience not have been worth it? If I’d died?” If neither mother nor baby die, does it mean horror can ratchet up to levels that would be unthinkable in everyday life, and it’s all fine?

She suggests such thinking “informs the delayed epidural, the women left to moan in corridors, the friend who gave birth in a hospital cleaning cupboard”.

Some attitudes are breathtaking. A doctor told Marianne “pleasantly” that pain trying to have sex 18 months on from childbirth “wasn’t something of concern”.

Marianne would like to see better training for healthcare professionals, but, she said: “I suspect that all the training in the world isn’t going to make a huge amount of difference in a healthcare system that is chronically underfunded and understaffed.”

Her memoir charts sleep deprivation, loneliness while never being alone, anxiety, feeling she’s a bad mother. It’s hard, she avers, to speak of some things to people who don’t have children, and even to other parents.

“How to say, to someone who has confessed how much they want kids, that you fear everything you were, that you are, has been bulldozed by the task of looking after your swiftly conceived, healthy, beautiful baby?”

Marianne wants inclusivity for mothers and babies, instead of being “hidden away in our homes and our groups and our special cafés, our corners of the internet, corners of the park”.

Her reports from the coalface of motherhood will strike a chord with all parents. She classifies, humorously, the various types of yucky mess parents deal with; writes of the perennial advice dished out; the passing stranger’s gleefully uttered: “Your baby needs a feed”; of being addressed as Mum at the clinic.

The memoir highlights difficulties grappling with paid work and childcare. The latter could be split 50/50 with her husband, Marianne writes, but it’s not, because logic dictates that it falls on the part-timer, the lower earner – her, the mother. Income shrinks. “Every pound of what I would earn until they went to school would be spent on childcare… often, quite a lot more.”

She told Review: “We need better shared parental leave and paternity leave, and more affordable childcare. As a society we need to step up; if we believe in equality of the sexes then we have to pay for these things via our taxes. Otherwise, it is women who suffer.”

Marianne, who was an actor and voice artist in her 20s – at one time her room in a shared house backed onto the main line out of King’s Cross – has written children’s books and now mixes arts journalism and features with essay writing.

Although she had read “two great motherhood books”– A Life’s Work by Rachel Cusk and Making Babies by Anne Enright – Marianne said that before having her children she hadn’t given great consideration to what being a mother would be like.

“Very few books seemed to attempt to truly describe the experience, at least none that I could find. Don’t Forget To Scream is my attempt at this.

“It is my fervent hope that the book can break down the barriers that exist between those who have had children and those who have not. And I hope that it might embolden other mothers to speak out about experiences of their own.”

• Don’t Forget To Scream: Unspoken Truths About Motherhood. By Marianne Levy, Phoenix Books, £14.99