Look back on anger

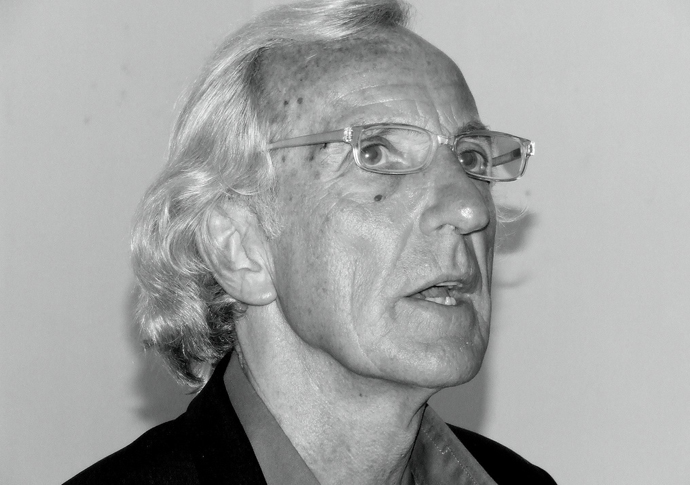

Filmmaker Christopher Hird remembers a champion of the underdog, the Australian journalist John Pilger

Thursday, 8th February 2024 — By Christopher Hird

John Pilger: October 9, 1939-December 30, 2023

IN his book Distant Voices, John Pilger tells the story of an encounter early in his career as a war reporter. He had just seen and touched a victim of napalm – the chemical weapon dropped from the sky in industrial quantities by the Americans in their war on Vietnam during the 1960s and 1970s.

For those whom it did not kill, the flaming chemical stuck to the skin and left horrible disfigurement.

As John reports, the smouldering skin came away from the victim’s body, sticking to his hand. John had seen the American plane drop the bomb on a village path and so, a few days later, he had some questions for the American spokesperson at the press conference.

John asked the official whether he had ever seen a victim of napalm and received a look of blank incredulity in return.

John then asked him what was the meaning of a phrase which had been used earlier in the press conference – there had been “collateral damage” in the bombing. He received another stare and was asked to rephrase the question.

John repeated the question twice and the official said that it meant that people had been killed. Does that mean “civilian people”, John asked.

In a barely audible voice, the official said: “Yes.”

This event left a profound impression on John as it crystallised ideas which had been forming in his mind for some time and which were to drive his journalism for all his life. What he saw in front of him was a pleasant man doing his job, devising language to disguise the reality of what was going on. People, as he put it, of “apparently impeccable respectability” who – because of their physical and cultural distance could – without regret – kill and maim civilians and destroy communities.

He resolved that his journalism would not allow people in power to separate themselves from the consequences of their actions. And he would not collude in hiding unpleasant truths.

Many journalists will have made such resolutions to themselves privately but few have been so successful in sustaining that determination throughout their career.

We got a sense of where this came from in the eulogy at John’s funeral last month. When he was a child in Australia he asked his parents which side they were on in an election then being held. “We are on the side of the underdog,” his father replied.

And that was John’s instinct – small countries being crushed by big ones, the Kurds being slaughtered by the (US and UK backed) Saddam Hussein, the miners fighting to save their communities in the face of privatisation, indigenous peoples resisting political and economic oppression and, of course, Julian Assange.

But there was another story told at John’s funeral that resonated.

He was a keen rower, making it to the first eight at his school. However, as a state school, the boat was not allowed to compete in the prestige local competition. John started a campaign for them to be allowed to compete.

It was a success and to John’s great satisfaction his boat beat that from the smart private school. John was an intensely competitive person. He never gave that up, either.

It is all these qualities which made John so effective – that enabled him to get his journalism into tabloid papers like Daily Mirror and his films onto big broadcasters like ITV.

He was a campaigning journalist but facts and research were at the heart of it.

At Dartmouth we produced his last four films and he would do an enormous amount of reading and research before we even started pre-production.

This is what made John such a formidable opponent in an interview – you get a taste of this in his forensic examination of then US Assistant Secretary of Defence in the film The War You Don’t See. And why people had to pay attention to his films and written journalism.

But this was not to everyone’s taste.

Establishment journalists did not like it at all. In 1991, Sir Robin Day refused to present him with the Richard Dimbleby Award for broadcasting excellence and Dimbleby’s son David said that John was not a broadcaster “in the sense that the award was meant”.

In the present day there have always been people who accused him of lacking nuance, only telling one side of the story and, in particular being obsessed with the ills of American foreign policy and not of, for example, Russia.

But this is to misunderstand what drove John on. As Martha Gelhorn said of him, it was “his anger about the state of the world” – and, on top that, his anger that the much of the media was in a silent pact to recycle narratives which provided only a partial (in both senses of the word) account of this.

As he said at the top of his website: “It is not enough for journalists to see themselves as mere messengerswithout understanding the hidden agendas of the message and they myths which surround it.”

• Christopher Hird, founder of Dartmouth Films, worked with John Pilger for many years