Red, white and… black all over

‘At Arsenal, what is going on in the pitch is always a small microcosm of what’s going on in the community’

Friday, 11th October 2024 — By Tom Foot

Dr Clive Nwonka, centre, with Femi Koleoso, broadcaster and Olympian Jeanette Kwayke, former Arsenal players Anita Asanta and Paul Davis at the launch event for Black Arsenal [Annabel Staff]

WHAT does it mean to you to be an Arsenal fan?

The answer is not so easy to put your finger on.

“People just simply know why they have a connection or appreciation of the club,” said Dr Clive Chijioke Nwonka, a professor at University College London. “Really it’s quite innate, unexplained. People find their connection in their own kind of way, but it’s always going to be there.

“At Arsenal, what is going on in the pitch is always a small microcosm of what’s going on in the community.”

Dr Nwonka is the co-editor of a collection of essays about the club, Black Arsenal.

The book includes contributions from Ian Wright, Paul Davis, Femi and TJ Koleoso, Clive Palmer, Paul Gilroy and Gail Lewis pitching the club as having a unique story in black British history.

But this is far from simply a walk down memory lane or a roll call of great black players to play for the club.

The book looks at Arsenal’s “deep cultural resonance” with its fanbase which played a role in shaping progressive anti-racist views across north London.

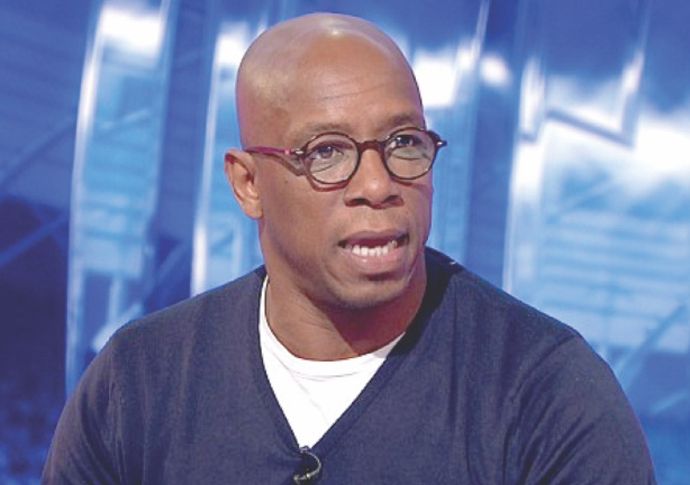

Things began to change with the emergence of Ian Wright at Arsenal as “the first poster boy of the Premier League” – something Dr Nwonka described as “transcendent” of race – in the early 1990s.

“I was a Liverpool fan, from John Barnes,” said Dr Nwonka, 42.

“What I realised looking back on it all was that when I got to the early 90s there was a different kind of black masculinity that was becoming appealing.

“It wasn’t any more the well-spoken John Barnes, with his military-type background. It was Ian Wright, with his gold tooth, coming out of an estate in south London – he had a different kind of swagger to him.

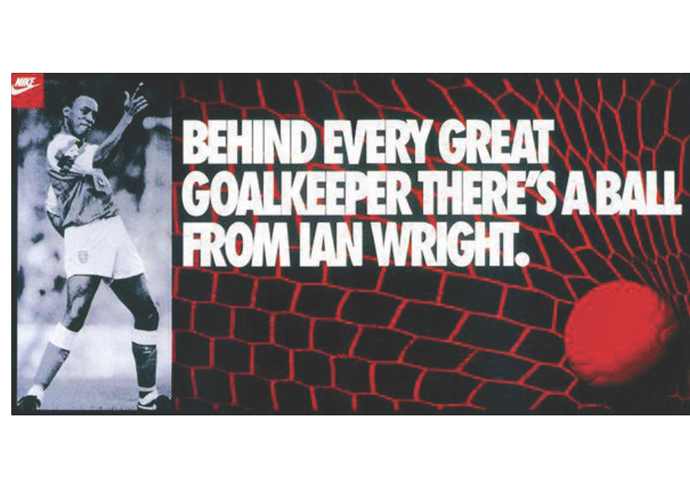

Ian Wright changed the game on and off the pitch – he was chosen for Nike ads and is still a TV regular [BBC]

“It was a swagger that was replicating the kind of life on housing estates that I was used to growing up in north-west London, in Dollis Hill and round Harlesden way. It was when Arsenal really started becoming synonymous with black identity.”

Dr Nwonka’s book examines how the Arsenal generation of black players which preceded Wright – Paul Davis, Raphael Meade, Michael Thomas – paved the way for him achieve that stardom.

Of Thomas’s famous title-winning goal in 1989, he writes: “Television – so often complicit in the racist characterisation, the historical reduction and erasure of Black people – was here key to heightening of black Britishness as a visible presence within popular culture.”

And the book looks at how Wright in turn set the stage for Patrick Vieira, Thierry Henry and now Bukayo Saka.

But his impact, Nwonka said, went far beyond his goal-scoring prowess.

“With his emergence in the Premier League came a new visual culture,” said Dr Nwonka. “All of a sudden, for example, you had this ‘Can I Kick It?’ Nike advert, featuring Wright and a hip-hop soundtrack from the New York-based rappers A Tribe Called Quest.”

The writer said there is something about the “access point” Wright’s presence created for black people – a period when what was going on on the pitch really started to reflect the life on the streets around Holloway and Highbury, Archway and Camden.

Dr Nwonka said: “It became a leveller for so many people. You had white Irish kids wearing an Ian Wright shirt.

“Of course just having this doesn’t resolve all the problems. You could still love Ian Wright, and hate black people – but some things are suspended. That multi-culture you see at matches, it impacts what you see beyond the stadium, through the surrounding areas.

“That’s why in my research I did a lot of walking up the Holloway Road, trying to soak up what it means to be an Arsenal fan. I think you don’t get that in other parts of the city, and other parts of the country.”

The book in no way suggests that the fight against racism was won in the 1990s thanks to Ian Wright.

In his essay in the book, Dr Gilroy writes: “It seems that many people still find the idea of being simultaneously black and British an impossible, unthinkable combination.”

He writes about the treatment of Saka after the penalty miss for England in the Euros final – “freshly cast in the old English drama that assumes black players not only to be bottlers but considers them a gang of unwelcome intruders who lack the bulldog qualities rehired for authentic membership of the national community”.

Dr Nwonka’s book looks at the concept of “self policing” on the terraces and how it stopped the far right from infiltrating.

“People seem to forget Islington had its own far-right issues. There are pictures of NF book stalls in Islington in the 1970s,” he said.

“The multicultural thing we have today, that wasn’t always the case.”

Arsenal released yet another away kit this season – one that says it “honours the strong connection between Arsenal, north London and Africa”.

The kit’s price tag is £85 – or £110 for the “authentic” version.

“I am often asked how I feel about the question of exploitation,” he said.

“Are Arsenal exploiting black culture, through the shirts they make? Firstly, people often conflate black culture with black people.

“When you think back to when we were growing up, you’d have one match a week. You had Shoot magazine. Now it’s different with a new generation of football allegiances based not just on proximity but also on who has the best social media content on merchandise.

“That’s the way football fandom works now. There is a new emerging fan base that isn’t going to be what the white working class of north London were interested in back in the day. I do believe Arsenal are doing this in an ethical way.”

The book looks at the controversial story of the original North Bank mural, a giant image of fans that concealed construction of an all- seater stand in the former Highbury stadium in 1992 – but had no black faces.

Bukayo Saka [Pedro Soares / SPP]

“Kevin Campbell [the late former Arsenal forward] – grace his soul – told David Dein that it was unacceptable for the club to have that,” said Dr Nwonka.

“Me and you both know there are many clubs that would still do that even today, an no one would bat an eyelid.”

After an outcry, the mural was replaced with one that “looked like the fanbase”.

He spoke too about the impact of AFTV on social media and the rise of “black fans talking about the game”.

But surely other football clubs, particularly in London, could make the same claims about black identity?

Dr Nwonka said: “I don’t think I could write another book like this for any other club in the world. I genuinely think that, because what you would be doing is reducing its black representation to players on the pitch.

“Any club can do that, but how does it manifest beyond football.

“That’s what the book is about. There is a football club but also a deep cultural resonance that other clubs can’t influence in the same way, and that’s what made it fascinating for me.”