Review: Icons of Cinema – Greta Gerwig

As Laura Venning’s new book illustrates, Barbie director Greta Gerwig has become a figurehead for female film-makers, and a wonderful voice in cinema

Wednesday, 24th December 2025 — By Dan Carrier

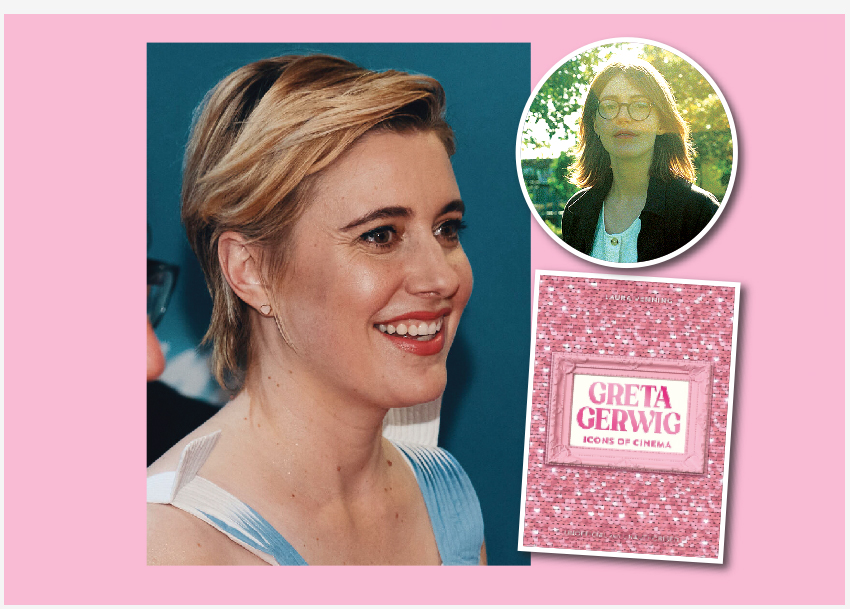

Greta Gerwig at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival [Frank Sun_CC BY-SA 4.0]; inset: Laura Venning [Alex Krook]

Greta Gerwig has become something of a figurehead for a cinematic movement of female directors. We still are in a world where directing is male-dominated – a situation that at its heart is odd, considering stories about humans are no doubt best told by the humans they focus on.

In a new, quick-read biography of the actor, writer and director, Islington-based author Laura Venning offers a primer to this most dynamic and interesting film-maker.

Laura is a freelance film critic and this is an unauthorised biography of Gerwig. While this means she doesn’t have primary sources on Gerwig to draw on first hand, she has lovingly crafted a walk-through of Gerwig’s film career from the front row and as a fan.

Gerwig’s clamber upwards to a bona fide global film powerhouse began as an actor that came to define the down-played Mumblecore genre – an early noughties movement that focused on listless 20-somethings negotiating the years between adolescence and adulthood.

Laura creates a timely reminder of the landmarks this film-maker has had in her career, and is a primer that links movies such as Hannah Takes the Stairs (2007) through to Barbie (2023).

Gerwig was born in Sacramento – a place described as “California’s Mid-West”, and not in a nice way – lacking the glamour of Los Angeles or the hip of San Francisco. Her mother was a nurse and her father worked for a credit union.

In a whistle-stop run through her childhood, we hear she was into ballet and then street dance, wanted to study acting but moved to the east coast and chose English and philosophy instead, as it felt a more employable degree.

Film lovers have benefited from this – her works are intelligently scripted and have a commentary of the vagaries of the human condition throughout, from her acting in Frances Ha, a story of platonic friendships and loyalty, through to Barbie and its take on gender relationships.

We also learn that early on she was a fan of the great Hollywood films, her hero being Gene Kelly: as a child she was taken to see The Muppets Take Manhattan and had to be forcibly stopped from attempting to climb into the screen to join in the fun herself – a telling moment, it appears, as she would eventually clamber into celluloid as a vehicle to tell stories.

She has always represented a particular type of yearning in her films, and her role in Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha came to represent a very New York sensibility and seemed to herald her as a mouthpiece for an indie intelligentsia.

More importantly, Laura says Gerwig has spoken “about how so many women have experience projecting themselves onto stories about men because the overwhelming majority of stories, especially ones deemed important, are by and about men”.

In 2017, Gerwig moved from in front to behind the camera, and the result was a worldwide hit that illustrated her originality and intrinsic sense of how to create a story that felt very real.

Lady Bird – drawing on her own Sacramento childhood – helped her form a group of actors she saw as a stable of like minded talents: Saoirse Ronan and Timothée Chalamet, who would return to work for her again. Laura says Gerwig wanted to build up relationships in the same way Wes Anderson, Robert Altman or David Lynch has done so with a trusted group who get her aims and style, and come to represent it in the viewers minds.

Gerwig’s breakthrough came via the Mumblecore trend – a genre that many found highly irritating, while others loved it.

Mumblecore can best be described as a genre that relied on a variety of elements – low budgets and hand-held cranky camera work, improvised scripts and often completely plotless, focusing on college graduates trying to find meaning in their lives as adulthood kicks in.

The issue with Mumblecore was the apparently attractive kookiness could flip the other way and be highly annoying, staffed with characters who don’t realise their privilege. Perhaps it is a testimony to Gerwig’s acting abilities that she could conjure up love from some sections of her audience, and a sense of frustration from others.

We learn that her breakout movie was Greenberg, a 2010 film made by Noah Baumbach, who she would later marry. It was time to move on from Mumblecore – and besides, as Laura adds, “the shaky cameras made her feel queasy”.

Laura clearly loves Gerwig-isms – the narrative tells a story that rises ever upwards, but without having access to the director, there are questions that are not asked, and therefore Laura is drawing on sources such as simply watching Gerwig films.

Her criticism carries the narrative. Greta Gerwig is a wonderful voice in today’s cinema, and this tribute to her shows why.

• Icons of Cinema: Great Gerwig. By Laura Venning. Bonnier Books, £13.99