River phoenix: how to revitalise the capital’s waterway

In his book about the Thames, the late historian Andrew Saint called for a major reappraisal of the river

Thursday, 5th February — By Peter Gruner

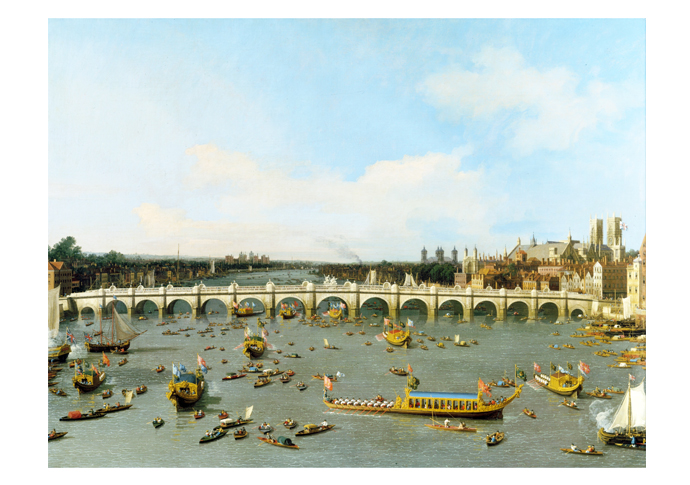

Canaletto’s most famous view of Westminster Bridge, painted three years before the bridge opened and showing Lord Mayor’s Day, 1746 [Yale Center for British Art via Wikimedia Commons]

IT was often called “The Bridge of Sighs” due to the high numbers of desperate people who sadly used the river to take their own lives.

In Victorian times there were also fatalities involving people who met their deaths in the river when they were tempted to “play” on floating timbers or so-called defective vessels.

The book’s author, leading architectural historian, Andrew Saint, a former Camden resident, called for a major reappraisal of the river and how it can help improve life in today’s capital and be a boost to tourism.

Sadly Andrew, 78, who previously lived at Dartmouth Park Hill, died in July last year, just a few months before the publication of his authoritative book, Waterloo Bridge and London River (Investigations and Reflections).

The book begins in 1952 with the then famous photo of Labour politician Lord Noel-Buxton, 35, former Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries, attempting to walk across the river from Westminster Bridge. He was, he declared, trying to trace a Roman ford, a so-called shallow crossing point. But it didn’t end up the way he had hoped. Six feet three inches tall, the lord, wearing just a shirt, pullover, flannel trousers and gym shoes, let himself into the Thames from the Surrey side at low tide, and attempted to walk across the river watched from the banks by a small but growing crowd.

Author Andrew Saint

However, he waded no further than the first pier of the bridge when the waters closed around him and he had to swim to the other side. Still wet and teeth chattering, he attended a Labour Party meeting later that morning.

Andrew writes that most of those who leapt from the bridge or waded into the river from its stairs were young women, while it was mainly men who perished on dodgy vessels.

American-born Alice Blanche Oswald, not yet 20, became famous in 1872 after jumping from the parapet and screaming for help when she hit the water. Oswald left a long letter expressing her hopelessness and destitution. It turned out that she had first gone to Australia to work in a hotel and when that didn’t work out came to Britain. Andrew believes that her death may have finally triggered a new pragmatic approach to suicides. Not long afterwards, a floating police station was established on an embankment just east of the bridge.

With easy access, the Thames was always a dangerous place.

“Boys in particular loved to lark about on boats and floating timbers, to leap or swim riskily between them,” Andrew writes. “Often they ended up crushed or drowned. Frequently bodies were dumped surreptitiously in the river – murder victims sometimes no doubt, more often inconveniences or embarrassments whose funerals might otherwise have had to be paid for.”

Andrew laments today’s lack of the freight-filled craft of yore, including the lighters, barges and tugs. He finishes the book complaining about the “appalling standard of architecture besetting the tideways on both sides of the river. That is especially true below Tower Bridge. There are few exceptions. It cannot be for lack of money, since many of the monstrosities are apartment blocks for the rich. Have we become so blind to beauty? For shame, London.”

• Waterloo Bridge and London River: Investigations and Reflections. By Andrew Saint, Lund Humphries £29.99