Rookery nook

From a leper hospital to ‘Tin Pan Alley’, the parish of St Giles-in-the-Fields boasts a colourful history. And now a new book brings it vibrantly to life, says Dan Carrier

Thursday, 8th August 2024 — By Dan Carrier

The church of St Giles-in-the-Fields seen from the air

MEMORY, the authors of a new and brilliantly encyclopaedic book on St Giles say, has not been kind to this patch.

But as their intricately researched but lightly told history of the area reveals, St Giles has everything; a microcosm of London development, it reflects how a city evolves over centuries.

As Rebecca Preston and Andrew Saint reveal in St Giles In The Fields: The History of a London Parish, St Giles has enjoyed a reputation – and in this history, they consider why.

St Giles runs from Tottenham Court Road in the west to Southampton Row in the east: it begins around Torriano Place in the north, and stretches down to the southern end of Drury Lane.

The story begins with a leper hospital founded by Queen Maud, the consort of Henry I, in 1117. The area was outside the city walls so deemed suitable – and St Giles was the patron saint of lepers, hence a name that has lasted 1,000 years.

As London grew and St Giles was consumed by the city, it quickly became a byword for overcrowding and poverty. It meant pestilence was never far away: the Black Death stormed through the small alleys in the Elizabethan period.

Diarist Samuel Pepys recalls “two or three houses marked with a red cross on the doors, and ‘Lord Haveth Mercy Upon Us,’ writ there, which was as a sad sight to me, being the first of the kind that, to my remembrance, I ever saw.”

The Civil War saw enforced changes: Parliamentarians recruited 9,000 men, women and children of St Giles to help build defensive works through the neighbourhood to defend London from Royalist attacks.

By the late 1700s it was called the Rookery – and this moniker reveals plenty.

A Rookery was a colony of unruly people, based on the idea that “birds of a feather flock together”. It was also linked to the well-used verb “to rook” – which meant to cheat.

The Bow Street Runners called it the Rookery in police reports, for another reason.

St Giles had long drawn in the poor and vulnerable, people in need of a cheap place to stay. St Giles attracted scores of American War of Independence veterans and escaped slaves. Londoners called these American emigres the Blackbirds – creating another link to the Rookery.

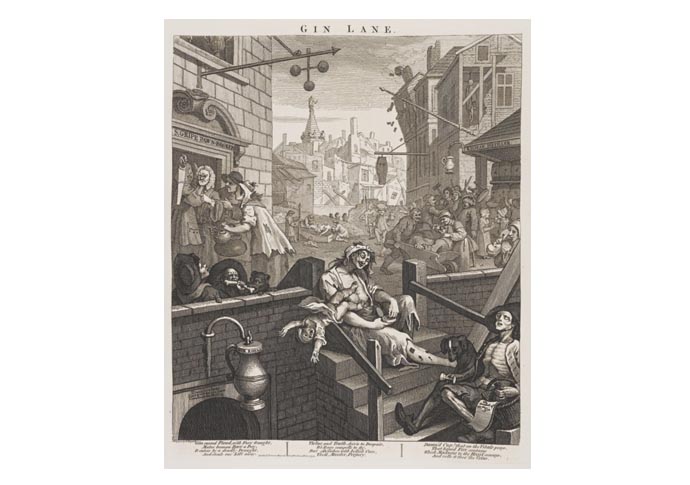

The authors have drawn on a wide range of great sources: the story of Saunders Welch provides eyewitness accounts of life in the 1700s. He was a Bow Street Runner and the Constable of Holborn in 1745, and in a rather unique position to keep tabs on the goings on – he also owned a grocers in St Giles and spoke at length about the criminality and prostitution. Hogarth was his friend and it led to his famous illustration, Gin Lane, which highlighted the rampant alcoholism many were afflicted by.

Hogarth’s famous depiction of the parish, Gin Lane

As well as overviews of trends – who lived there and why, how they earned a living, the industries, entertainment and much more besides – the authors have picked out illustrative stories that bring these Londoners to life.

We hear of the tragic tale of Anne, Countess of Castlehaven, who lived in Betterton Street – where today’s Denmark Street can be found.

In 1631, her husband, the Earl of Castlehaven, was tried and convicted of sodomy – he was accused of buggery with a servant – and raping his wife, who he held while his servant assaulted her.

For these crimes he was beheaded. It was a sensational case, with an extra layer of intrigue due to the fact the Countess had a claim to the throne.

St Giles, over many decades, became home for Irish emigres, which in turn caused the area to suffer from a blanket of racist attitudes towards them. Records show a large Catholic population from the 1580s onwards – and this in turn leads to persecution and raids, where residents would be censured for not attending Church of England services.

But while the area had a reputation for the low skilled, unemployed, criminals and beggars, it also hummed with industry. There were workshops and factories, breweries, scruffy pubs and gin dives, restaurants, cafés and music halls, theatres, painters, engravers and printers.

Breweries were a major employer. St Giles churchwarden Richard Bigg established a brewhouse, mill and pub that eventually became The Horn Brewery in West Central Street. It was taken on by the Hucks family, who became brewers to the king, and was but one of a number of industrial brewers with capacity for many thousands of gallons.

The Meux Brewery, on the site of what is now the Dominion Theatre, was the scene of tragedy in 1814. The hoops around a 22ft-high vat of 3,555 barrels of porter split and beer, weighing in at over 570 tons, flooded out. It smashed its way through walls and spilled into homes in St Giles. Eight women and children died.

Among the many shops were scores of bird dealers – songbirds created a cacophony around Seven Dials, Monmouth Street being particularly busy.

In the 1690s, a James Kendrick advertised canaries and bullfinches for sale at the Black Lyon in Drury Lane, while “Safron The German Birdman” advertised fine turtle doves and talking parrots.

Fish, reptiles and amphibians could also be bought, while hedgehogs did a lively trade – they would be kept in kitchens to eat beetles and other pests. Costing one shilling, they were said to be affectionate to humans and made good pets.

While Denmark Street became known as “Tin Pan Alley” by the mid-1930s, home to music publishers and producers, its musical roots go further back.

Music publishing can be traced back to the Musical Bouquet, a weekly Victorian publication that printed songs and piano music. Later, Denmark Street had multiple publishers operating from its upper floors, while instrument sellers and workshops took on ground floors and backyard studios.

A four-storey factory on the site of the Phoenix Theatre in Charing Cross Road built pianos for Chappells Music. It burned to the ground in 1860.

Smaller workshops could be found dotted around Great Russell Street and Tottenham Court Road.

In Store Street, piano-maker Robert Wornum built a music hall. Aged 50 when he set up the hall, Wornum was the innovator who came up with the idea of the upright piano, which took Victorian parlours by storm. He built the concert hall for recitals on the instruments.

This hefty work of social history covers so much in a highly readable way. Preston and Saint have brought alive a slab of Camden in rich and relatable detail.

• St Giles In The Fields: The History of a London Parish. By Rebecca Preston and Andrew Saint, Brown Dog Books, £27.50