Rout with the old…

On the verge of yet another general election, Emma Goldman casts her mind back to 1997 and the country’s last Tory annihilation

Thursday, 4th July 2024 — By Emma Goldman

AS voters go to the polls today after well over a decade of Conservative rule and a likely Labour win, I am reminded of the last time this was this case: 1997.

Back then, I had just started teaching. Now I am a veteran.

In 1997, education and health services had been wilfully underfunded for years. But I had long since left any seat of learning and my parents were not yet ill and so this knowledge for me was theoretical.

Then I started applying for teaching jobs.

The more literary the name, it turned out, the grimmer the place.

Thus, the ‘Geoffrey Chaucer’ school, then featured in the press as one of the worst schools in Britain, was a sprawling mass of cracked windows and barbed wire fences. ‘William Shakespeare’ school was a jumble of tower blocks and black railings with barred windows. Under government special measures, nervous breakdowns suffered by its staff were so common that those afflicted were simply referred to as being “on mad leave”.

Indeed, popular belief was that the only people to get jobs there were unsuspecting newly qualifieds and a scattering of “apostles” who saw it as their mission to go in and “save” the pupils.

My first job was temporary: two terms in a north London boys’ comprehensive on a lane close to where I lived. In the 1990s, the media presented inner-city teenage boys as at best potential muggers and at worst hardened criminals. It used to be that I had considered crossing the road each time I saw a group of boys from this school.

But they had always parted silently to let me through. One day I vaguely came to think of them as courteous.

Perhaps it was my mentioning that to the stressed-out head that swung the job for me. Or perhaps it was that I was the only applicant.

He told me I would be teaching in “the Huts”.

“The Huts?”

“They’re not part of the main building. They’re down there, over by the edge of the playground.”

On my first frosty morning, I stood in one. A broken heater whirred. A strip light flickered on and off. Suddenly, there was a crash.

Two 15-year-old boys charged in through the door. The first leapt up onto one of the Formica tables that acted as desks. He was followed by another who flung his bag across the floor, jumped onto a chair next to the window and wrote in big letters on the wall one word: F***.

“Who are you?” the first one asked, looking down at me.

‘‘I’m your new teacher.”

He jumped off and collapsed into a seat.

‘‘’Ow are we supposed to learn with new teachers all the time? We got GCSEs next term. This place is shit, man.”

In the English department, selecting which books to teach KS3 (11- to 13-year olds) each term meant rifling through battered, dated novels in cupboards. Even for the GCSE students, we had no money left for exercise books and worked on sheets of paper. Then parents held a jumble sale and bought some.

Yet from all year groups in the freezing Huts, a common call over the scraps of paper, din, and text books shared between three was: “I wanna learn, man.”

After the election, things changed. Sudden funding brought shiny new copies of wonderful fiction to the shelves.

It brought exercise books. Come summer, the rickety huts were pulled down and a new build commissioned.

Across inner-city secondary schools, exam results rose. The fast-track system was created. Passionate young teachers arrived from top universities.

All too late for my GCSE class.

Now, after a decade and a half of austerity, there are parallels.

The school where my friend works in outer London has teachers from departments as wide ranging as Geography and PE covering English exam classes during free periods because it has no money to replace the teacher who left.

Also, as in 1997, staff turnover there is high. Staff turnover breaks the bond between teacher and student.

Students become resentful and disconnected.

In the press, rundown 1997 echoes in other ways, too. The narrative is simplistic. Everything is “the parents’ fault”. All bad behaviour must come from home. We should fine parents if their children truant.

Capitalising on this inclusive approach, Rishi Sunak has a new shibboleth for the children themselves: cannon fodder. That should improve their attitude.

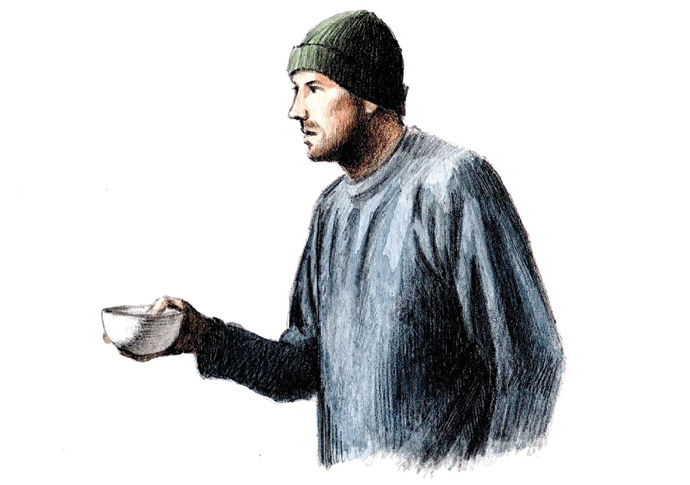

I was reflecting on all this the other day when I was on the tube. A Hogarthian beggar shuffled along the carriage – not an unusual sight. But as he held out a hand for change, his eyes lit up.

“Miss Goldman!”

I stared at him.

“Don’t you remember me?”

He was one of my original GCSE students from the Huts.