Wagner: the musical revolutionary ‘with a huge head’

Despite having a huge influence on the latter decades of the 19th century, the German composer wasn’t too popular with many of his contemporaries, writes Neil Titley

Thursday, 13th February 2025 — By Neil Titley

Richard Wagner in 1861

WHEN Whiteley’s of Bayswater ceased operating in 2018, it closed the door on generations of famed customers. Few were more illustrious than the German composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883).

While in London to conduct The Flying Dutchman at the Albert Hall in 1877, he took the opportunity to cross Hyde Park and investigate the department store. He left clutching a rocking horse.

The concert itself was not entirely successful. His fellow composer Ethel Smyth was present and said of Wagner that he was “an undersized man with a huge head, apparently in a towering rage from start to finish of the concert – no doubt the performance was insufficiently rehearsed”.

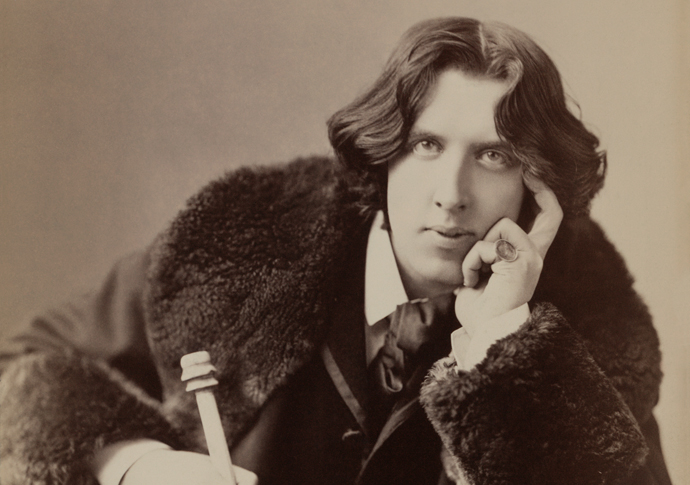

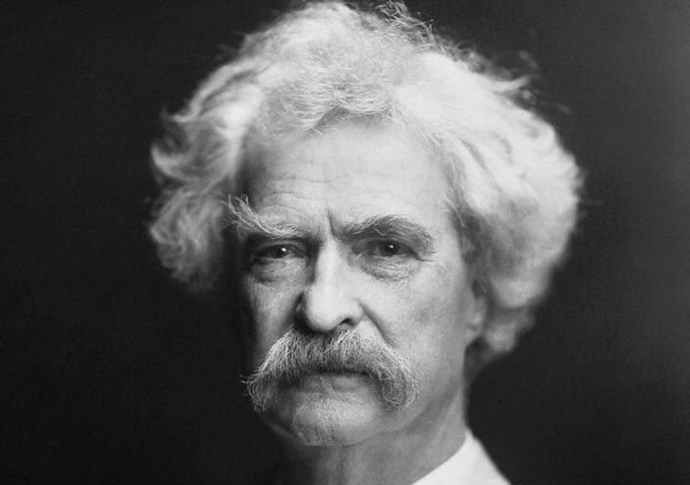

Her ambivalent attitude echoed many of Wagner’s contemporaries – Rossini described his music as having “lovely moments but awful half hours”. Oscar Wilde commented: “I like Wagner’s music better than anybody’s. It is so loud that one can talk the whole time with nobody minding.” Mark Twain was more consolatory: “Wagner’s music is better than it sounds.”

Despite this, he had a huge influence on the latter decades of the 19th century. Although then regarded as a musical revolutionary, his work was more of a culmination of German romantic music than the start of a new form. Debussy said of him: “Wagner was a beautiful sunset that has been mistaken for a sunrise.”

Oscar Wilde

He had begun his professional life as a jobbing conductor and by 1848 he had completed three operas, The Flying Dutchman, Lohengrin, and Tannhauser. He had intended calling the latter work Der Venusburg until friends pointed out that the title, “The Mount of Venus”, might lead to ribaldry. He hastily renamed it.

His career was interrupted when in 1849 he joined a revolutionary group called the Young German Movement and became involved in street fighting against the authorities. He was forced into exile from Germany for the next 11 years, much of this time being spent in Zurich and the rest in conducting his work around European cities.

He relied a lot on female company and had numerous affairs throughout his life. This led to attacks on his libidinous nature as well as on his art. The Irish professor John Mahaffy: ‘‘Wagner was an unutterable cad and should have been hounded out of all decent society.”

A supporter of Schopenhauer’s gloomy view of humanity, Wagner’s real character lay in his utter egocentricity – a capacity to ignore or overcome any scruples or even common sense if they interfered with his artistic genius. He refused to compromise in any way. The staging of his works required huge expenditure including building an entirely new theatre to suit their performance. (As Wilde said – “music is the most expensive of all noises”.) In order to stage The Ring, Wagner needed a patron of enormous wealth and doglike faith. Amazingly, such a man existed.

Mark Twain

Prince Otto said of his brother King Ludwig II of Bavaria that, while he himself had lucid intervals: “Ludwig was always mad.”

Except for servants, Ludwig lived alone in his three castles. Occasionally he would send for musicians, but they were not allowed into the buildings themselves – they had to play out in the open. The writer Gertrude Atherton reported that when Ludwig had violent toothache even the dentist was not allowed entry: “Ludwig stuck his head out of a lower window, and the dentist standing out on the terrace pulled the tooth as best he could.”

Ludwig’s saving grace was his appreciation of Wagner’s genius. By 1864 Ludwig had opened the Bavarian treasury for his friend to spend what he wished on opera. This generosity was not greatly welcomed by the Bavarians. Given the strong rumours circulating that their homosexual young king was in love with the aging composer, the burghers of Munich insisted that Wagner leave the country.

Broken-hearted, Ludwig was forced to banish Wagner. However, he still managed to supply most of the money that funded the building of Wagner’s dream – a new theatre in the quiet Bavarian town of Bayreuth – and the first production there in 1876 of The Ring of the Nibelungs.

Rossini

Wagner introduced new ideas of staging into his project – he insisted on darkening the auditorium during performances and hiding the orchestra from view in a pit. There was a small design hiccup before the first show. The dragon used for the combat with Siegfried had been built in sections in London. The neck did not arrive in Bayreuth in time for the show as it had been wrongly delivered to Beirut in the Lebanon.

Slipping unnoticed into a rehearsal before the first performance of Das Rheingold, King Ludwig sat alone in the darkness breathlessly watching the one great achievement of his life. Ten years later, having gone completely insane, Ludwig drowned himself in the Starnberger See. The body of his psychiatrist was found on the nearby shore with its head smashed in by a heavy stone.

Allegedly Wagner died of a heart attack in Venice in the middle of a row with his wife Cosima over his advances to a Flower-Maiden in the cast of his last opera Parsifal.

• Adapted from Neil Titley’s book The Oscar Wilde World of Gossip. www.wildetheatre.co.uk Available at Daunts, South End Green.