When we set about ‘making trouble’

As women’s groups fought for housing, work and childcare in the 1970s – and against the ‘Miss Islington’ contest – Lynne Segal was in amongst it all, writes Daisy Clague

Friday, 7th November 2025 — By Daisy Clague

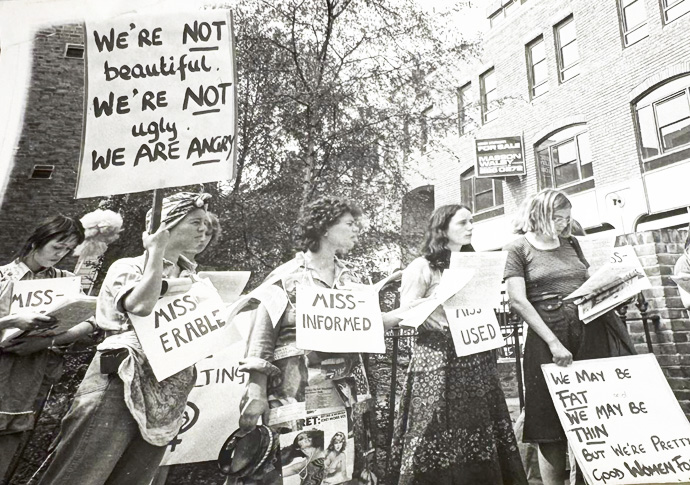

Feminist campaigners oppose the ‘Miss Islington’ beauty contest in the 1970s

LONG before the Tribune published its first issue, local left-wing and feminist activism was documented by the Islington Gutter Press from a squatted building on the corner of Balls Pond and Essex Road.

It was the 1970s, and nothing seemed impossible.

Feminists from groups in Highbury and Arsenal set up a women’s centre in York Way and later Essex Road, where they organised around housing, work, childcare and women’s health.

Others created local feminist theatre groups, picketed the Miss Islington beauty contest, staged a sit-in against the closure of the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson hospital, and campaigned against the pin-ups that still adorned the Islington Gazette.

In amongst it all was socialist feminist Lynne Segal, then a single mother newly arrived from Australia, who moved into a house in Highbury in 1971 and set about “making trouble”.

Sitting in the same house this week more than 50 years later, she told the Tribune: “What was happening for the first time was the idea of valuing women. Women just were not valued before women’s liberation. I so strongly inherited the idea that only men were important. It was a very different world to now.”

Before long Ms Segal was sharing the house with two other single mothers and their children, and it has remained a space for communal living ever since, with rotas for cleaning, cooking and childcare.

Roughly 40 people have called it home over the years and even now, at 81, Ms Segal shares with four others.

In the early days some of her biggest influencers quickly became friends – feminist writers Sheila Rowbotham, Barbara Ehrenreich and Judith Butler.

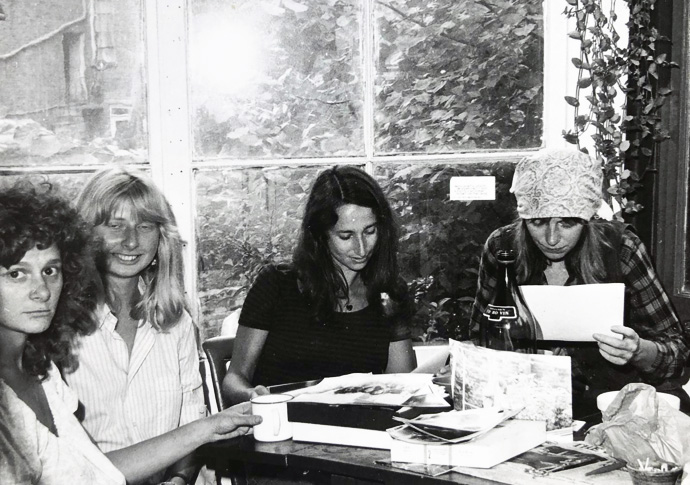

Ms Segal’s Highbury home in the 1970s

“And we were all influenced by Simone de Beauvoir, obviously. Many of us had her picture on the wall,” Ms Segal added.

The Women’s Liberation Movement emerged in the late 1960s from the male-dominated New Left – “that anti-Vietnam, anti-war politics of the 1960s” – and saw women and grassroots politics coming to the fore.

“Grassroots politics, participatory politics, a huge emphasis on democracy and a suspicion of leadership, that’s what we took from the revolutionary politics of the 1960s,” said Ms Segal.

“I describe myself as a socialist feminist because there’s always a danger to me that the word socialism disappears. Socialism wants a better world for everyone. Its ideals are to be inclusive.”

Her commitment to socialist politics put Ms Segal at odds with so-called “radical feminists” – a stereotypically “anti-man” strand of feminism, in the lineage of today’s trans-exclusionary radical feminists (TERFs).

“If you’re a socialist, obviously the fundamental enemy wasn’t men,” she explained.

Despite the many victories of 1970s feminism, questions about who or what a woman should be are by no means a relic of the past, with trans people now particularly under attack for their identities.

Ms Segal said: “I just feel so sad that feminists wouldn’t be able to understand why it is that some people don’t feel they can slot into the gender they’re being positioned in. For a trans woman to have felt they cannot live in the way that men have been situated, seems something that feminists should welcome. I can’t see why feminists wouldn’t welcome it.”

Ms Segal (right) on a Gaza peace march

In 1979, Ms Segal wrote a pamphlet called Beyond the Fragments with friends Sheila Rowbotham and Hilary Wainwright, initially published by the Islington Community Press in Balls Pond and Essex Road.

In anticipation of a Thatcher government, it was an appeal for unity and solidarity that called for alliances between feminists, trade unionists and other left movements, which is still relevant today.

“If we’re going to defeat what is, again, an incredibly frightening rise of the right, as we saw at the end of the 1970s, we need to be part of a wider movement,” said Ms Segal.

“One that everybody’s been inspired by is Zack Polanski, and then many people have always been inspired by Jeremy Corbyn.”

On Mr Corbyn’s new political project, Your Party, she added: “The solidarity never goes far enough. I think Corbyn tries to be as open and inclusive as possible, but there is an inbuilt tension between those around Corbyn who want him to be leader and, no doubt, those around Zarah Sultana, Andrew Feinstein or Jamie Driscoll, beginning to feel excluded.

“They have to have a party and try and get seats in parliament, I understand that, but things go wrong so quickly as you try to set up these inevitably hierarchical structures. The contradiction is that we want to look up to people and to get some leverage on power you have to have people in [leadership].

Lynne Segal has just been expelled by her local Labour Party after 40 years of membership

“But I don’t think we should have Your Party standing against a Green Party member, or against anyone who’s progressive in the Labour Party. People want purity in politics, but that’s not what politics is. We really need to think strategically around how we fight the conservative forces of the moment, together.”

Ms Segal’s own desire for solidarity on the left is not one echoed by the local Labour Party, from which she was expelled last week after 40 years of membership, over a photograph of her smiling with Corbyn campaigners before the general election more than a year ago.

Ms Segal said: “It’s fine. I mean, I think they’re so wrong, they should welcome me. It shows them being threatened, doesn’t it?”

She added: “A lot of people had said, ‘How can you still be in the Labour Party?’ But politics is complicated, and I think anyone should be wherever they feel they can, to be a progressive force.”

Part and parcel of her feminist activism is Ms Segal’s support for Palestine, and she is a stalwart of the Jewish bloc on the regular Palestine solidarity marches through London. And though now retired from her formal work as a lecturer, Ms Segal has no plans to slow down.

“I’ve been reading more on friendship and its significance in politics,” she said.

“Politics isn’t just about asserting power and being aggressive. Love and friendship are central to politics.

“Ideas spread through people – they’re about people having places to stay and putting each other up.

“It’s very much what consciousness raising and feminism were all about: making contact, sharing your outlook, creating a more visionary politics.”