‘Anger can make me fight for change, for things to improve, and attitudes to shift’

Doctor who was injured at a shopping centre says disabled people are being impaired by society

Friday, 30th May — By Tom Foot

Grace Spence Green made national news when a man fell on her from three storeys up as she stood on an escalator, breaking her back and spinal cord

SWIMMING in the Kenwood Ladies’ Pond is one of the few times Grace Spence Green can “really breathe out”.

The Hampstead Heath sanctuary is where she goes to get away from the endless crass questioning and peculiar behaviours that have plagued her since her injury at the Westfield shopping centre, Stratford, in 2018.

Aged 22, her back and spinal cord were broken by a man who fell on her from three storeys up as she stood on an escalator.

A former South Hampstead School pupil, she was at the time living on a houseboat with her boyfriend and halfway through a medical degree.

The shocking event was national breaking news and there were months of follow-ups and think-pieces frothing over fixed narratives that she feels barely touched the surface of her nuanced story.

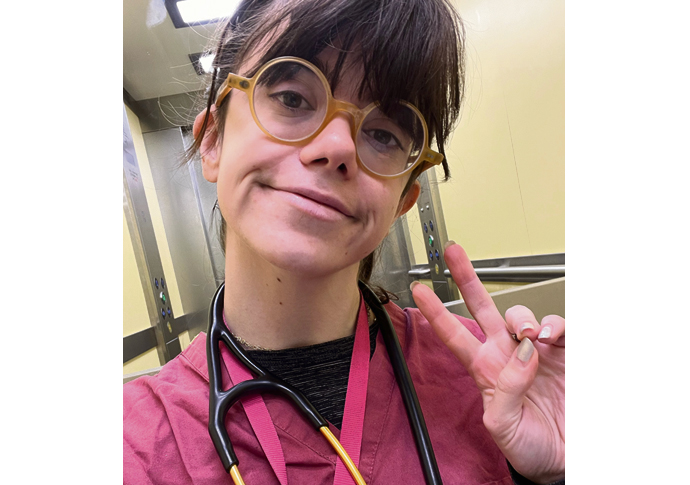

Ms Spence Green, a junior doctor soon to start specialist training in paediatrics, has written a book asking people to think of disabled people as a community impaired by society rather than their injuries.

It looks at the roots of the pressure she came under to either hate or forgive the man that fell on her, the “inspiration porn”-style disability comeback stories prevalent in the media, people’s inability to understand that “independence as a fallacy” and the demonisation of the wheelchair.

Perhaps most importantly it makes you think about why people are unwilling to get their heads around what Ms Spence Green describes as her “radical acceptance”: simply being content – as the title of her book says, To Exist As I Am.

Ms Spence Green, a junior doctor who is soon to start specialist training in paediatrics, has written a book about attitudes towards disabled people

Being an object of ableist pity has been one of the hardest things for her to deal with – “how many more gasps and wide-eyed faces can I take?”

“Maybe I could understand a pitying reaction better when I was still stuck in hospital, but it continued to crop up, even once I was out in the world, doing a dream job that I had worked so hard for, beginning to enjoy life again, and feeling more capable every day in my new body.

“I want my story to be seen in the context of a greater struggle of generations of disabled people. In the community where I have found a place. I want it to be bigger than myself and part of a movement of collective action and solidarity that we can all play a part in.”

Now back living in Clerkenwell where she grew up, Ms Spence Green says there are basically two narratives of disabled people in this country: individual victims striving to walk again; or the Paralympian “superhero”.

“It’s useful as it individualises our struggle, takes us out of the societal and political context, putting the onus on us as people to live up to these impossible ideals.”

There is difference between the medical model of disability “where it’s your job to fix it”, and the social model “that society is what disables you mostly rather than the impairment”, she said, adding: “It’s a difference between thinking, I can’t go there because I can’t walk – to thinking, I can’t go there because they haven’t built a ramp.”

Over the years, she has come to think of her wheelchair as something of a fun friend, as well as fundamental to her independence. She writes about feeling powerful in the chair that lets her “be swift and nimble … turning sharply, gliding down slopes …”

Ms Spence Green, pictured on Hampstead Heath, says being an object of ableist pity has been one of the hardest things for her to deal with

Ms Spence Green talks about a media obsession with how she felt about the man who fell on her, a routine line of questioning when she appeared on breakfast TV or in the national press to talk about disability rights.

“They started using it as a reason to say ‘look what cannabis does to people’,” she said. “They were using me for their political ploys. There were weird racist undertones – the guy was black, he was an immigrant. ‘Look at this poor white woman!’”

The book has some darkly funny passages about people’s behaviour, ranging from an ultra-safe tip-toe approach to the insanely unthoughtful, like the couple of drunks thudding at a pub toilet door laughingly disbelieving that she was really disabled.

“Sometimes frustration still overwhelms me,” she said. “But anger I can cultivate. It grows into confidence, into boldness, into fearlessness, it makes me do things I never thought I could do. It makes me want to fight for change, for things to improve, for systems to change, and attitudes to shift.”

Perhaps the most significant passages in the book are devoted to the community of disabled people she has met along the way and the campaigners and writers that have preceded her.

“I learned how activists and pioneering thinkers are dismantling ideas like productivity and normality, to reinsert disabled people into the spaces that have excluded and erased us,” she said.

She writes about “minute but radical acts” of care that are the “antithesis of capitalism”, adding: “When someone lifts me into a car, helps me out of the shower, when I hold my friend’s arm to help her balance, we are not here to make a profit or a product. We are here for each other.

“Caring goes against everything society seems to be hurtling towards. In a world that feels like it is becoming more and more hostile, to be kind is a profound act.”

Up at the ponds, Ms Spence Green has particular praise for the kindness of a Lithuanian lifeguard, Tanya, who helps her into the cold water from a plinth. “She used to be a professional synchronised swimmer and has been teaching me to be a stronger swimmer all year,” she writes.

“I enter the freezing water and suddenly all my body has to do is stay alive. Five minutes before I get in, my mind is wiped clean. Everything that at first was so hard, has become softer, easier.

Opening my eyes to this new reality used to be so exhausting, to feel so bitter, like the cold that used to make my bones ache. But now, it’s true. I am more than OK.”

• To Exist As I Am is published by Profile with the support of the Wellcome Collection in Euston.