Rave new world! Author celebrates music scene’s key figures ‘written out of history’

Ray Kinsella’s book tells of ‘overlooked producers, DJs, promoters and revellers’

Friday, 27th June — By Daisy Clague

Ray Kinsella with Islington Museum exhibition co-curators Sarah Guzman and Tory Turk

IT was 1988 when Ray Kinsella first heard the music that would change everything.

“I was listening to pirate radio one night – it was like, what is this squelchy, weird, acidy sound? It was mad. Nobody had heard music like that before.”

Acid house music blew up in London during the late 1980s, brought here – so the story goes – by four British men after a lads’ holiday in Ibiza, where they were inspired by Argentinian DJ Alfredo’s mix of house and disco during an ecstasy-fuelled night at the club Amnesia.

But in his forthcoming book, Clubbing Culture in Islington, 1986-1995: Ravers and Junglists, Mr Kinsella challenges this prevailing narrative as “just one story” of how acid house, house, rave and jungle scenes emerged in the UK.

“I was part of the early rave scene when I was 15 or 16, and I used to see people I knew from Islington DJing at a lot of the events,” said Mr Kinsella, a lecturer and writer who grew up on the Packington and Marquess estates, and got his academic education in later life through a once weekly English course that led to a degree, MA and PhD.

“But when I started reading the history of that time, a lot of those people were overlooked and I wondered why. The story was quite white-washed, for one – the music came out of black and LGBTQ+ communities, and that’s been written out of the history.

“For two, when it was embraced here, it was embraced and made by everyone – black people, white people, LGBTQ+ people, straight people. I knew there was another story to tell about the scene.”

Mr Kinsella’s research connects the emergence of this new music with the diverse communities of Islington, where blues parties, shebeens, dub and reggae mixed together in the borough’s five square miles and dozens of clubs like Turnmills, EC1, Paradise and Rocket popped up from Clerkenwell to Holloway Road.

“The book is a celebration of the overlooked producers, DJs, promoters and revellers that contributed to the acid house and early rave scene that paved the way for the jungle and house scenes that dominated club culture in Islington in the 90s,” he said.

Mr Kinsella has also joined forces with the Islington Museum to bring the wild nights of yesteryear to life in an exhibition of memorabilia items that will be collected from Islington ravers themselves.

Co-curator Tory Turk explained: “The rationale is to highlight that what people have under their beds, in their attics, at their dad’s garage, that’s the stuff now that museums are interested in collecting. It’s showing people that everyone’s histories are important.

“It could simply be a raver giving the little detail about how they got ready in a time before mobile phones, how they met up. For me, it’s about educating kids now who don’t understand those references because we live in a completely different world.”

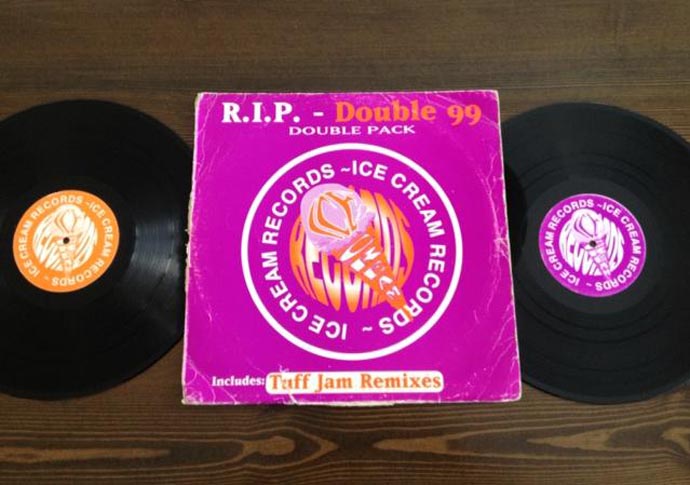

So far, the museum has been sent an original acid house smiley face T-shirt from the late 1980s, contributed by Chelsea Berlin; and an Ice Cream Records LP from 1995 sent in by one of its founders, Andy Lysandrou.

The label’s first studio was in a basement on Holloway Road.

A jacket that will feature in the Islington Museum exhibition

Traditional stories about that era paint it as a “romanticised coming together” of ravers across racial and class divides, Mr Kinsella added, but there was still a lot of division.

“I don’t want to rain on the parade – it was an amazing time for me as well – but it was still rough, it was dangerous. When people come together and swap ideas it does create something new, but when they leave that space and they come down off the E, the opportunities aren’t the same for everyone. Just because you meet somebody in a rave, it doesn’t mean they’re going to give you a job.”

And by 1995, that radically different music scene “became absorbed into the mainstream”, Mr Kinsella said.

“What started out as a grassroots thing becomes appropriated and then marketed back to the people for a price.”

This was, in part, due to a “moral panic” about drug-addled young people – John Major’s 1994 Criminal Justice Bill gave police new powers to crack down on outdoor dance festivals and music “characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats”.

And in some ways, it was also the story of Islington itself, as a new wave of gentrification in the mid-1990s saw derelict warehouses converted into loft apartments and the clubs being pushed out.

Mr Kinsella said: “Nightclubs make places attractive in the first place and bring in property developers, and when they redevelop it the people that have made it trendy move out. It’s just the way it is.”

Sarah Guzman, Islington Museum and exhibition co-curator, said: “This is the long view of the history of Islington.

“Where you have communities who are predominantly working class, that becomes attractive and then it gets built up – guess who can’t afford to live here anymore? I think the vibrancy of Islington is something that maintains, but it gets pushed into different corners.”

• Islington Museum is still sourcing rave memorabilia for the exhibition – contact islington.museum@islington.gov.uk by July 31.