‘There was this strange sense of magic that the Henrions left behind’

Film-makers Harriet Atkinson and Sue Breakell tell Dan Carrier how a chance encounter opened the door to the world of Henri and Daphne Henrion

Friday, 31st October 2025 — By Dan Carrier

Dr Harriet Atkinson and Sue Breakell outside the Pond Street house

THE Pond Street house was more than a home for the Henrion family: as well as providing a haven for generations, it would be a hive of activity, a place where the look and feel of mid-century Britain was shaped via the work of the two artists who lived there.

Henri – or FHK – and Daphne Henrion bought the home in 1947, and now the story of how the house became a period-defining design studio has been told by two historians.

Dr Harriet Atkinson is a Kentish Town-based academic. With her University of Brighton colleague Sue Breakell they have made two documentaries about the life of Henrion, whose work ranged from Ministry of Information posters during the war through to corporate logos that remain in use today.

It was while making Art on the Streets (2023), a film telling the story of the anti-fascist artist movement, the Artists International Association, that Harriet and Sue came across the Pond Street address.

In 1942, FHK Henrion worked with other artists and writers to create an exhibition that celebrated Franklin D Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms.

Held in the bombed-out ruins of the John Lewis department store in Oxford Street, it included work by Oscar Kokoschka, Augustus John and captions written by Cecil Day Lewis.

They visited the house to film a piece about Henrion’s work for the association – and as they shot footage on the pavement, the door opened.

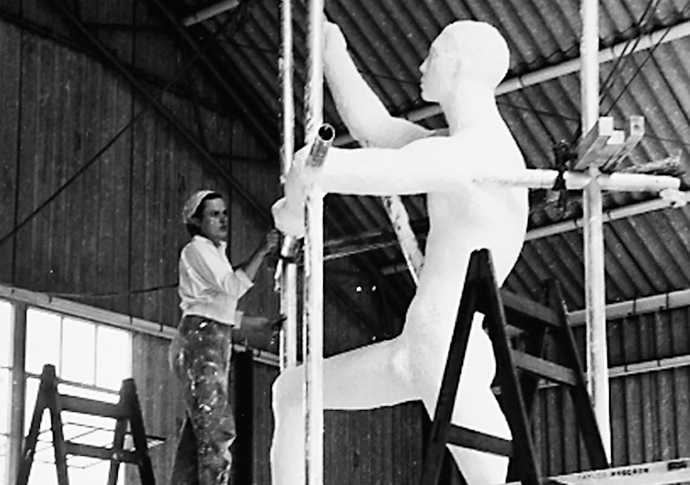

Daphne Henrion at work

“When I started the research for the first film, I went to have a look at his house in Pond Street,” recalls Harriet. “We started filming outside when the front door opened and a man asked what we were doing.

“I asked him if he knew that a famous designer had lived there and he said: yes, that was my father.”

Max Henrion, who is based in California, happened to be spending a week at his childhood home and he invited Harriet inside.

“We were very lucky he was visiting,” she says. “We went inside and there was this strange sense of magic that the Henrions had left behind – the colours of the walls behind the bookshelves, for example – there were things Henrion had put in place 50 years previously that were still there and offered clues to their work.

“I had written about Daphne before and I was interested in the relationship between the pair and their home, which they also used for work.”

It led to another documentary, Designing From Home.

Henrion lived in the same house for more than 40 years, until his death in 1990. He was an émigré who came with nothing, but became a high-profile designer. Daphne Henrion was a celebrated sculptor, whose work would grace the Festival of Britain.

As well as the house containing FHK’s studio and office for his design business, a large studio was built in the back garden, designed by the architects Norman Foster and Richard Rogers. Indeed, for a time the architects had a studio in the basement of the building. It provided Daphne with a huge workspace to create her sculptures.

Harriet focuses on artists’ archives and collections – the University of Brighton is home to Henrion’s papers. “I am interested in this generation of designers. So many made a real contribution to the UK during this period,” she says.

Henrion was part of an artistic movement, and he worked with other emigrés.

“Looking through our archives, you realise the connections between different designers and the people they designed for.

“There were individuals who worked together and inspired each other during this period. Henrion worked, for example, with Misha Black. He had come to the UK in an earlier wave of migration. Black designed things like the street signs in Westminster, on motorways and the Underground.”

This type of signage is vital, but being so common to the eye is often overlooked.

Henri – FHK – Henrion working at home. [Colin Tait, FHK Henrion Archive, University of Brighton Design Archives]

“I am really interested in how the everyday impacts – how designs that are seen each day are almost invisible, but represent this period so well,” she adds.

Henrion was born in 1914 in Nuremberg and moved to Paris in 1933 to train with artist Paul Colin, who appointed Henrion as his assistant.

It was while designing posters for the French Pavilion at the Levant Fair in Tel Aviv that he met members of the British Mandate. War was raging in Palestine and Henrion could not stay. He came to the UK and was put to work designing a poster advertising citrus fruits.

As fascism spread, Henrion acted. He joined the Artists International Association, the left-wing collective that brought creatives and politics together.

Despite his clear anti-Nazi bona fides, he was interned when war began for six months on the Isle of Man: the week he was released he contemplated how at the start of the week he had been deemed a possible enemy alien, and by the Friday was working at a desk in the Ministry of Information.

He would go on to create some of the most stunning pieces of graphic art of the period, wartime posters that encapsulated for the nation the shared struggles they were enduring, and giving voice to the struggle.

He recalled how he would cycle down to Bloomsbury to work each day at the Ministry, then based at Senate House, and spent time working for the US Army in Grosvenor Square, helping design magazines for GIs stationed in the UK. And when the Allies launched D-Day, soldiers came armed with numerous posters designed by Henrion to paste over the Nazi propaganda stuck on walls in towns that were set to be liberated.

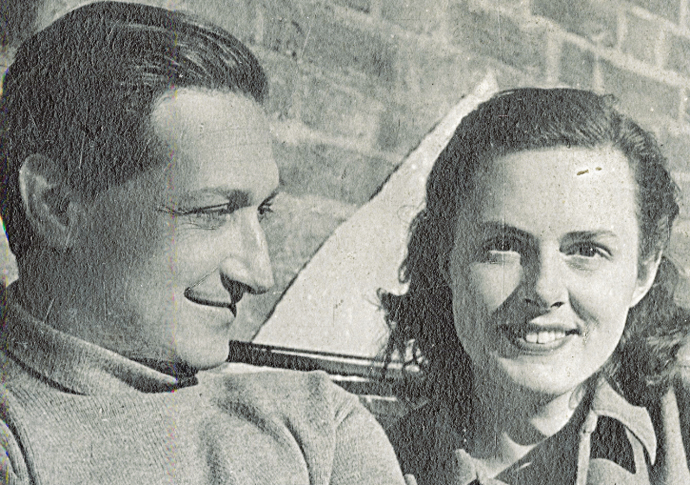

Daphne with Henri

In the 1950s Henrion designed corporate logos and helped invent the idea of a corporate identity. Some of his designs remain in place today and have become instantly recognisable – they include work for the National Theatre, Tate and Lyle and the Post Office.

“I wanted to consider his corporate work,” adds Harriet. “They are visually interesting and so familiar to so many. He proposed a particular way to present the corporate world though his work and show how businesses could present themselves

“This was alongside the fact he was politically engaged, and worked for CND and Oxfam, which illustrated his politics clearly.

“In a way, they were pragmatists. They worked on pieces that corporate culture needed to sell itself, but also identified social issues and thought about how to improve the world through art. He was a chameleon in that way.

“He worked for big organisations such as the General Post Office, and helped create a visual framework for the new Welfare State. His collection is hugely diverse – he was very prolific.”

And it all came from 40 years of working from home, she adds.

“We wanted to look at this house and the two really fascinating characters who used it as a base,” she says. “It became almost organic, always growing and changing to reflect the needs of the artists who lived and worked there.”

• There are plans for a screening in Hampstead of Designing From Home. Details to be announced